As turkey numbers decline, some are wondering if all those corn piles could be part of the problem

Turkey numbers are down right now, and that's no secret. The most troubling declines are in the Southeast, where some measures of poult recruitment show that hens aren't making enough little turkeys in the spring to keep flock numbers stable. In Georgia, for example, hens were producing an average of 4.5-5 poults each spring in the late '90s. Today, the state's poult-per-hen average is hovering around 1.5, below the 2-poults-per-hen number needed to break even.

Biologists agree that the causes for the turkey decline are likely varied. Habitat loss, increased nest predation, disrupted breeding patterns, and disease all seem to be playing a role.

(Don't Miss: Podcast: Should Turkey Hunters Worry About Gobbler Sperm Counts?)

But what if the corn you're putting out for deer and hogs is adding to the problem? In many states, including most of the Southeast, it's both legal and common to put out corn as bait for deer and hogs for at least part of the year. Biologists say it's possible all that bait is contributing to the turkey decline, and it could be causing problems in more ways than one. Here's how.

Aflatoxin

Aflatoxin is a naturally occurring toxin produced by the fungus Aspergillus flavus that occurs on corn. It occurs naturally in the environment and tends to build on corn as it lays on the ground. Why does it matter to turkey hunters? Because turkeys are among the most susceptible animal species to it. Aflatoxin as low as 200 parts per billion (ppb) can harm turkey poults by causing liver dysfunction and immunosuppression.

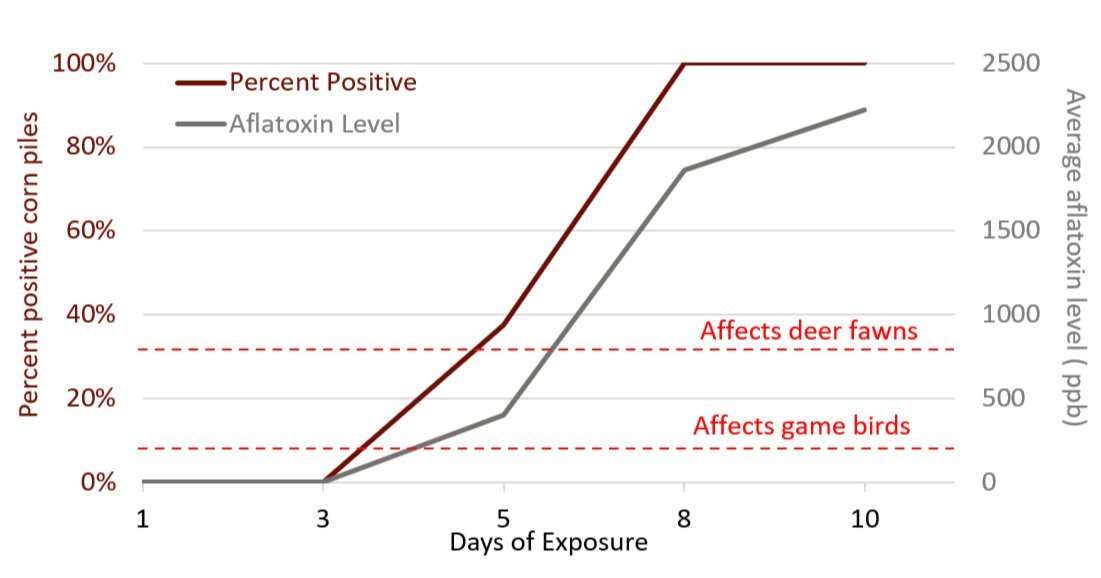

A recent study by the MSU (Mississippi State University) Deer Lab monitored corn piles placed on the ground during the summer and fall, the very times when young turkeys are out foraging to put on weight for the upcoming winter. All the piles tested negative for aflatoxin the first three days on the ground. But by the fifth day, nearly half the piles tested positive at an average concentration of 400 ppb. By days eight, nine, and 10, all of the piles tested positive with rates as high as 2,000 ppb, 10 times the rate that can harm poults.

"There is no doubt that aflatoxin can be harmful to turkey poults. We also know that aflatoxin builds up faster in warm, moist conditions, like corn placed on the ground in the summer and fall," said Dr. Michael Chamberlain, noted turkey researcher and Terrell Professor of Wildlife Ecology and Management at the Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources at the University of Georgia.

To make matters worse, corn sold as wildlife feed is often leftover or rejected stock that tested too high in molds or fungi to be used as human or livestock feed, so aflatoxin itself might not be the only issue causing problems. The specific corn we are putting out for deer or other wildlife could actually be more harmful. This MSU Deer Lab Chart illustrates just how quickly aflatoxin levels can build in corn piles placed directly on the ground.

Poor Nutrition

"Turkey poults are biologically designed to eat mainly insects over their first summer and fall," Chamberlain said. "That extra protein ensures they go through their first molt when they should and then go into their first winter in prime physical condition."

Yet, corn kernels are easier to catch than grasshoppers. "When the hen encounters corn, she naturally leads her poults to the easier food source and they consume it instead of foraging for insects," Chamberlain said. "Turkey poults that feed primarily on corn are slower to develop than normal, they don't molt as quickly, which means they don't develop flight feathers as early, meaning they roost on the ground longer and get exposed to predation longer. These poults also go into the winter with less body fat and in poorer overall condition than comparable poults who have foraged mostly on insects, which probably leads to higher winter mortality."

Concentrated Predators

Many biologists agree that nest predation is one of the main issues facing wild turkeys today. "We are seeing nest success as low as 20% here in Alabama, and nest predators account for a large percentage of the failed nests," said Dr William Gulsby of the University of Auburn School of Forestry and Wildlife Sciences. Dr. Gulsby is working with the conservation group Turkeys for Tomorrow on a research project designed to shed some light on why wild turkey populations are declining.

(Don't Miss: Are Turkey Seasons Opening Too Soon?)

Anyone who has ever put out corn for deer knows that it attracts raccoons, opossums, pigs, and other nest predators. "Nobody raccoon hunts anymore, and everyone feeds deer," said George Cummins, operator of Salt River Outfitters, a deer and turkey hunting outfitter in central Kentucky. "This has caused an explosion in the raccoon numbers. I find so many nests that have been raided I can't count them all. I think there's an unbalance in predators now, and it has slowly been increasing over the last 10 years. I run 60 plus cameras on over 20,000 acres in nine different counties and I regularly get photos of 20 or more, sometimes way more, raccoons on just about every camera."

It's not just the drop in hunting and trapping that is causing the boom in the predator populations; it might be that the corn piles themselves play a hand in it. "Think about it. Baiting concentrates predators in an area, but those predators, like raccoons, don't have to work to find food while bait is out. That means they go into breeding season in extremely good health, leading to increased litter size and decreased winter mortality rates, raising the population numbers even more," Dr. Gulsby said.

Couple these hyper-inflated predator numbers with decreased nesting areas due to large-scale habitat loss, and it's not hard to see just how difficult it is for a hen to successfully hatch a clutch of eggs.

How do We Fix It?

In the quest to conserve turkeys, it might be time to consider limiting or eliminating baiting for deer and hogs. Ironically, another rapidly spreading disease, Chronic Wasting Disease in whitetail deer, may make baiting issues with turkeys a moot point. At least 25 states have either changed or are considering changing baiting laws in response to spreading CWD.

Still, many hunters consider baiting to be an integral part of their hunting plans, so some states get extreme pushback to their plans to eliminate corn and other wildlife feed. What can we do in the near future while biologists, hunters, and politicians hash out the issue?

If you are going to feed, start by only using clean, livestock-quality corn, then use a feeder that keeps it dry and up off the ground.

For one, if you plan to feed deer or hogs, stop putting corn directly on the ground. "If you are going to feed, start by only using clean, livestock-quality corn, then use a feeder that keeps it dry and up off the ground. Set it so that only the amount of corn that will be consumed in a day or two is released, so that excess corn doesn't just lay on the ground," said Dr. Chamberlain. Next, wait as late into the summer or early fall as possible before putting out corn, so as to give poults plenty of time to feed on insects and prepare for the upcoming winter. If you hunt a large enough parcel of land, situate feeders well away from likely nesting and poult rearing cover to keep predators away.

When it comes to predators around bait sites, eliminate as many as possible during your state's legal hunting and trapping seasons. "Several studies have shown that predator control is beneficial to other ground nesting species like bobwhite quail, so it stands to reason that it should be beneficial to wild turkeys as well," Dr. Gulsby said.

Will ending baiting bring turkey populations back to where they were 10 to 15 years ago? Probably not by itself. As Dr. Chamberlain says, the turkey population decline is likely the result of a number of factors and the reasons may vary from area to area. But think of it like this: There are nearly 2.5 million turkey hunters in the U.S. What if we could all just save a poult or two per season?