Reflecting on a trip to Alaska, lessons in knot tying and landing fish, deer antler knives and more this Father's Day

Fathers are often the first teachers and mentors for their children in the outdoors. Here, three Realtree.com contributors and veteran outdoor writers who grew up in the woods and on the water look back on the gifts their fathers gave them — some intangible — that still have an impact today.

The Envelope

By Mike Hanback

Growing up in the 1960s I did what boys did back then: Tagged along with Dad every chance I got while he shot birds over his pointers (bobwhite quail for you literal types, but just birds to us Southerners), fished the back pond or just went for walks in the woods.

With Dad along, I shot my first squirrel with a single-shot .410. Caught my first bluegill and bass. Built my first driftwood fire down on the Rapidan River on a cold December afternoon, and boiled tea in a dented, blackened pot that Dad had carried around for years. It was the sweetest tea you ever tasted.

We didn't have many deer in my part of Virginia back then, barely enough to hunt. I'd go with Dad, and we'd sit for long, boring hours, and see maybe a doe (no doe season back then) but usually no deer at all.

Dad kept encouraging me, gently egging me on day after day and year after year, and because it's what boys did back then, I went with him and loved every minute, despite the cold, rain and misery of no success.

Then one crisp November day I finally saw a deer with spikes, a seemingly mystical beast. Somehow, I kept it together and shot the life out of the animal with Dad's old Winchester .30-30.

I was 12, 13 maybe. I remember being a little sad and a lot happy as we walked up to the buck. I can still see him lying there, still and staring up at me with glassy cat-marble eyes. Mostly I remember the feel of Dad's pat on my shoulder and the pride that shone in his eyes.

But you've heard all that, because that is what boys did back then. We grew up hunting with our pops, and that story has been told a million times.

It was something Will Hanback did for me later in life that cemented my desire to be a lifelong hunter and lover of the wild.

I had just graduated college and Dad walked up, shook my hand and stuck an envelope into it.

I smell grizzly, close, Melvin said matter-of-factly.

I figured it was maybe a hundred bucks. Dad was a carpenter, a good one, and made a decent living, but he was far from a man of means.

I opened it and found an airline ticket and a paid invoice for a two-week Dall sheep hunt in Alaska! Flying on an airplane…Alaska…kill a wild sheep… To this country boy, it was as foreign as going to the moon.

I can't accept this, I told Dad. The trip cost more than he could make in two months, maybe three.

Oh, you're going all right, he said. You can hunt all you want to around here, but until you've walked those mountains, you don't know what real hunting is.

How did he know? Dad had never been to Alaska; heck he'd never traveled west of the Mississippi. But he was a voracious reader and had devoured every book about Alaska he could get his hands on, along with countless magazine stories by Jack O'Connor and others about hunting big game in big, wild mountains. Those words and pictures were as close as he would ever get to The Last Frontier, but he made sure his only boy would go.

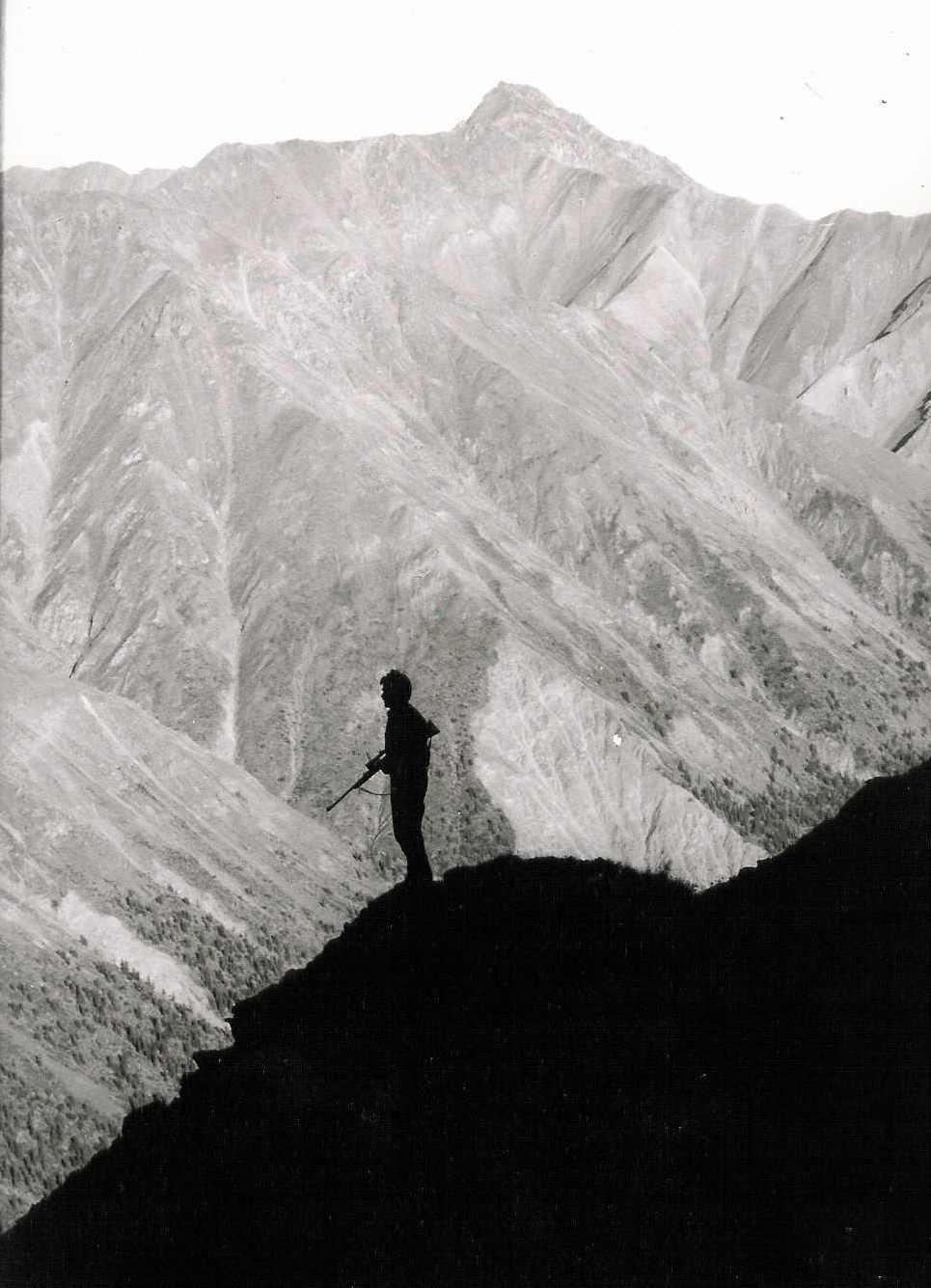

Fast forward to a sunny September afternoon 40 years ago. I craned my head and neck straight back, and looked up into the craggy tops of the Wrangell Mountains. Until I stepped foot into interior Alaska, I had no idea that God had created something so big and wild, so awe-inspiring.

Ready? Let's go, said my guide, Melvin.

It took 8 hours to hike to the top of the mountain, way above tree line to where the sheep was bedded. Eight hours of sweating, cussing, rock climbing, sliding, falling, bleeding, loving every minute of it. It then took Melvin two minutes to size the ram as a shooter, and me a few seconds more to line up and kill him with a 180-grain bullet.

I can still see the blood overspreading the ram's white shoulder, like you spilled a bottle of Merlot on your carpet. Then he toppled over and fell dead, rolling violently end over end in the rocks. Hunting back home I had seen the life and death of deer, but nothing so vivid, wild, and real.

Melvin gutted the animal, threw it over his shoulders and took off running and sliding down the talus as if it were an escalator from heaven. And in a way it was.

Halfway down the mountain I slung the sheep and went a good way with him to prove I was man enough to do it. Tough hunts in the wilderness make you do stuff like that. Four hours later we were back to the horses in the river bottom, and after a two-hour ride in the blackest night I had ever seen, we arrived at spike camp at 2 AM.

I smell grizzly, close, Melvin said matter-of-factly. The hair stood on my neck, but I was so tired I collapsed. I was still clutching my .30-06 with a 180-grainer in the chamber when we woke up a day later.

Fast forward to June 2021. As I sit here and write this, I am struck at how Alaska altered my life. I had plans to attend law school, but shortly after the trip, I turned to writing about hunting and the outdoors. It has turned into 40-year career that has taken me back to Alaska seven times, and enabled me to hunt in wild places all across North America.

Thanks, Dad, I miss you. I know you're looking down from a better place, somewhere way up high on a wild mountain.

The Lessons

By Steve Hickoff

My dad taught me to be patient waiting on turkeys, especially if the gobbler hit back hard when you called. This tidbit of wisdom has helped me every spring turkey season since, including this past one.

He showed me how to tie an improved clinch knot for attaching flies and lures and bait hooks. A fly tyer, he was something of a knot guy, and he even instructed me on the basics of a Windsor knot, used for formal occasions when you needed a necktie to dress up an otherwise grubby shirt.

I draw on that memory bank every year or so. Formal occasions are rare for me — taking the camo hat off is uncomfortable — but they're demanded of us all on occasion. I use the knot for a necktie I have with a half-strutting turkey on it, neck out, mid-gobble.

I use the knot for a necktie I have with a half-strutting turkey on it, neck out, mid-gobble.

As a guy who spends most of his time at the computer keyboard in a home office when not hunting, surrounded by my English setter bird dogs, not many ties hang in my closet. But that one connects me with a bunch of things, including my dad.

He even got me started on hunting dogs, with a beagle named Pokey (who was anything but), at age 11. His uncles had been Pennsylvania beagle men. Rabbit hunters. Like him. But ol' Poke also was keen on birds, too.

Dad led by example: gun safety, how not to get lost by picking landmarks, remembering them, and then following them back to the truck. I still do that, with a GPS and a compass as a backup if needed.

Like many of you who have lost a father, I think of him every day, surrounded by his fish taxidermy. A big smallmouth bass I caught on a banana-yellow popping bug on one of his visits to northern New England. An even larger brown trout I teased up to a Kelso wet fly he'd tied while visiting him in PA the last time we fished together.

Even then, he said, just as when I was a kid: Don't horse it, take it easy. I was a grown man of course, and smiled at that, him being so excited to see me land that fish. It's on the wall off my left shoulder as I type this.

The brownie taped out at 23 and 1/2 inches — I measured it several times — and weighed 6 pounds or so. A football, as they say.

My dad's finished wall mount of the big trout is nearly two inches longer.

As for the Windsor knot? I've a bittersweet memory of that. The last time I tied it was for his funeral several years ago. He would have thought that was funny, fitting, I promise you.

The Fillet Knife

By Michael Pendley

It was the darkest night in recorded history. That's how it seemed to my 12-year-old mind as I waited for the first glow of the sunrise. I was sitting on the ground, my back to a grand old oak easily four times my width. The overgrown fence row in front of me bisected a small pond just 25 yards away. The brushy strip served as a travel route between a picked corn field and nearby heavy cover, and the pond made a good stopping point for deer on their way from feeding to bedding down for the day. The break action 20-gauge in my lap was the same gun I carried on rabbit and squirrel hunts. But this time it was loaded with a shotgun slug. I was officially a deer hunter.

My dad had walked me to the spot earlier that morning. He left me with these words of advice: Be still and don't shoot unless you can see antlers. Back then Kentucky was buck-only except for the final day of season, a far cry from the unlimited antlerless tags available across much the of the state today.

The crack of a nearby rifle shot broke the morning silence, and I must have jumped a foot off the ground.

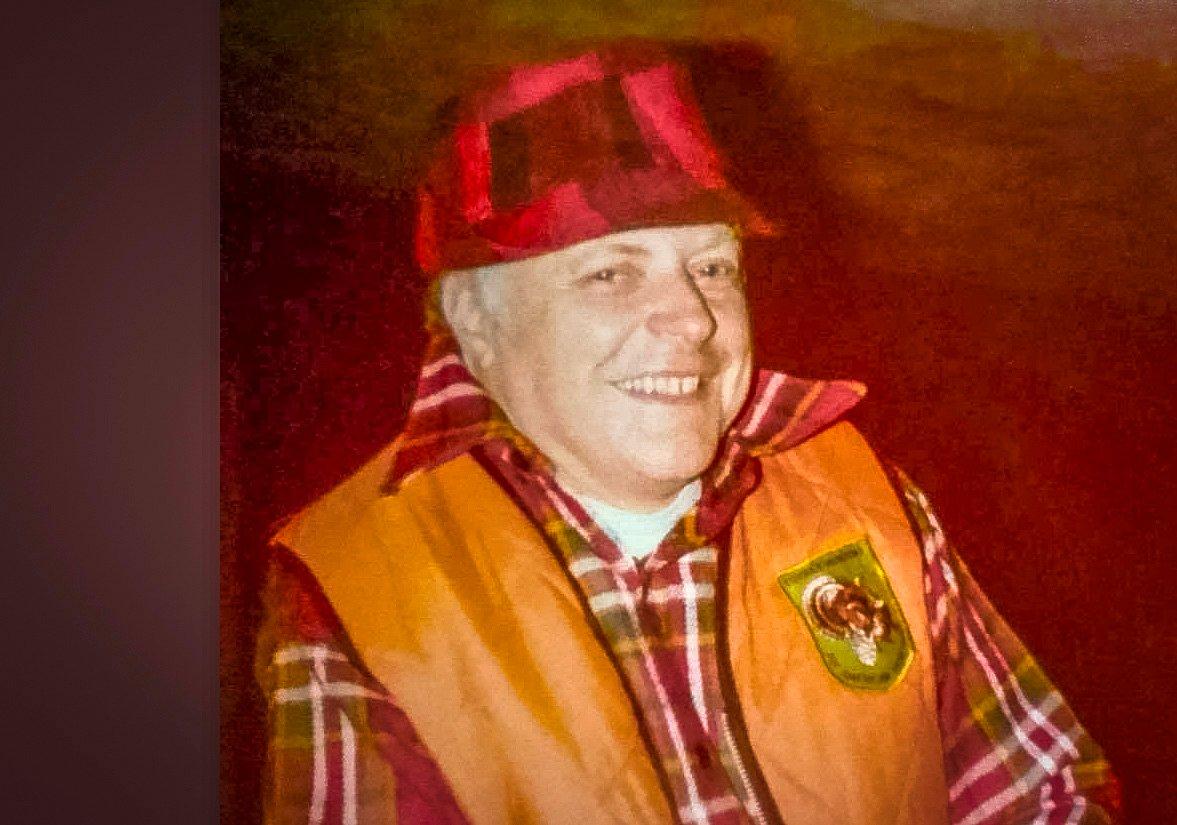

Just when I was certain that the sun had refused to rise, I noticed that I could start to make out the shapes of trees and brush around me. A few minutes later, the first pink light of morning appeared over the eastern horizon. When I was finally able to make out colors, I was comforted to see the orange glow of my dad's safety vest atop an abandoned oil tank platform just 200 yards away. He had found a spot where he could simultaneously keep an eye on his inexperienced son and watch for deer at the same time.

While no bucks made their way to the waterhole that morning, doe after doe slipped in for a quick drink before bedding down. With each new deer, I strained to make out an antler, any antler, atop its head, but Dad's words, make sure it's a buck, played in my mind over and again.

We'd been out two hours by then. The root under my butt had somehow grown 10 times in size since I'd first sat down and I found myself shifting, trying to get comfortable. The crack of a nearby rifle shot broke the morning silence, and I must have jumped a foot off the ground. I looked over at my dad to see if he would climb down from his perch to go get the buck I was certain he'd killed. After a few minutes, I saw him rise and walk down the stairs. Since he had cautioned me not to leave my spot until he came to get me, all I could do was wait. Soon, his red pickup rolled into the field and up the two-track dirt road to my spot.

My mind had filled with questions in the time it took him to get the truck and make it over to me, and I spit them out with machine gun speed. Did you shoot a buck? How big was it? Did it go down? He answered each, and by the time we pulled up to his deer, I knew that he had caught a nice 8-pointer slipping along the woods edge away from my spot, probably spooked by my constant fidgeting.

The buck was a good one, with tall, graceful tines that curved back toward center. It was a buck that drew a crowd at the check station in those days. When we got home, dad took a meat saw and skull capped the antlers before starting the skinning process. Aren't you going to get him mounted? I asked. His replied that you couldn't eat antlers, the meat was the best part.

Some time later, after the deer was wrapped and in the freezer, Pop cut the rack up and used the tines as handles for fillet knives. I still have a couple of them, and I still think of that hunt every time I pick one up.

(Don't Miss: 29 Father's Day Gift Ideas from Realtree)