Hearing loss is common among hunters, but it's not just because of gunshots. Here are some reasons you didn't hear that gobbler

It was almost midday, getting hot, and we hadn't found a turkey yet in the mood to cooperate. I'd just made a few excited cutts and yelps when my son Potroast jumped as if he'd been stung by a hornet. He scurried to a nearby tree and hit the ground.

Meanwhile, I just stood there, confused. Potroast looked at me like I'd forgotten everything I'd ever taught him about turkey hunting. Didn't you hear that gobble? he hissed. But I hadn't.

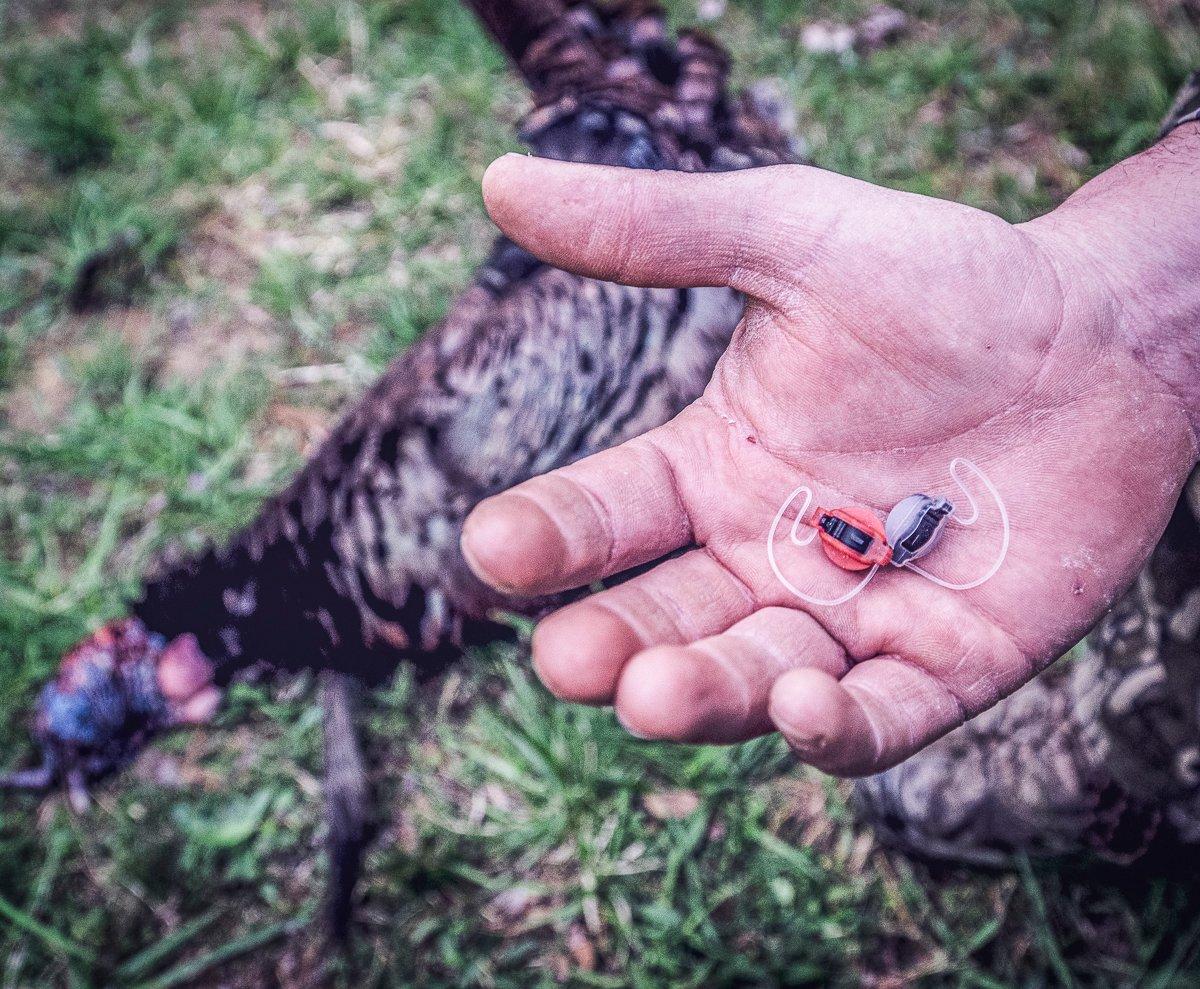

Still, I quickly hit the ground and hid next to a small clump of brush just as the bright red head appeared over the nearby rise. A quiet purr or two, and the tom was in range. He'd been that close when he cut loose. Potroast pulled the trigger, and the bird flopped to the ground.

I guess I knew, deep down, that my middle-aged hearing wasn't what it used to be. But the real-world implications of just how much I'd lost hit home that day. I decided to find out all I could about what caused hearing loss, how to prevent it, and what could be done once it occurs.

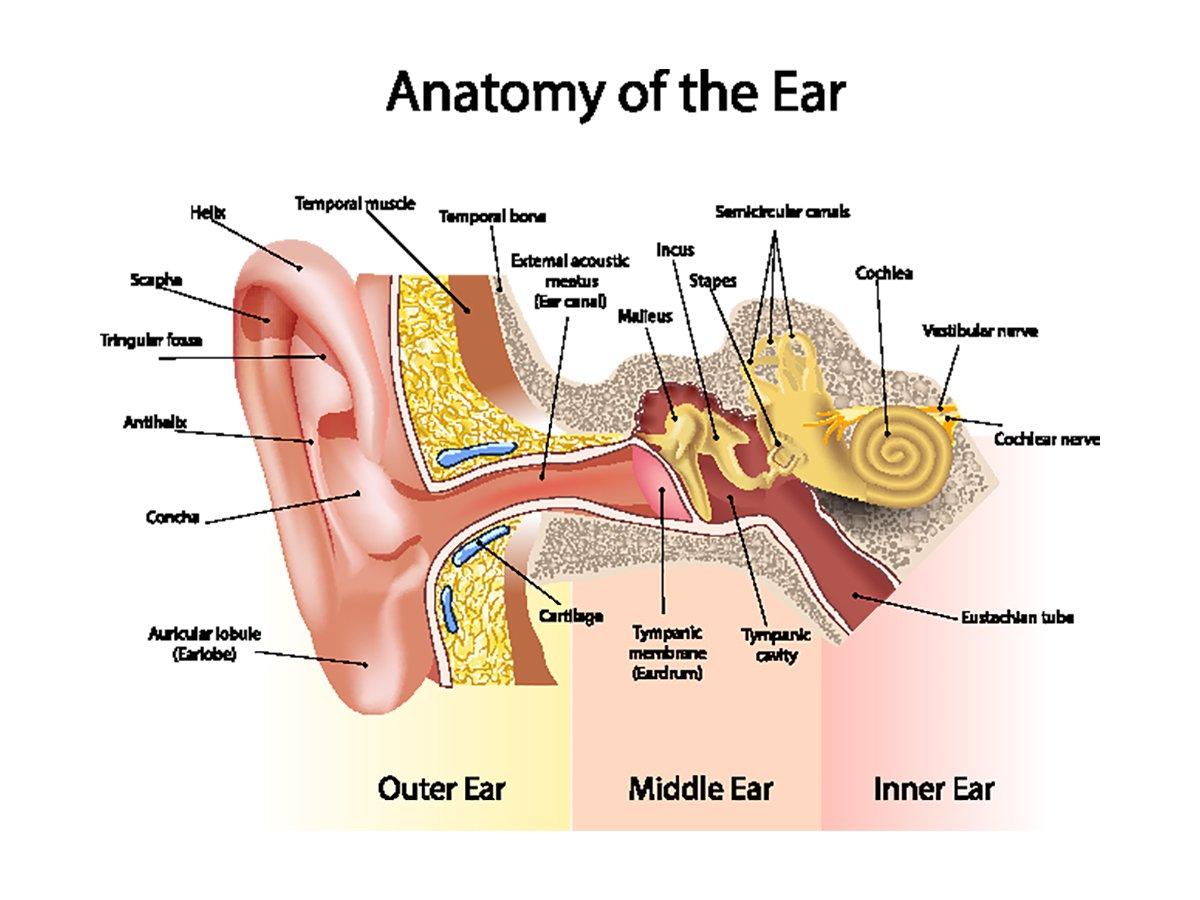

Here's How You Hear

Dr. Ron Shashy is particularly qualified to explain it. Besides being an otolaryngologist (an ear, nose, and throat doctor), he is a lifelong shooter and a helicopter pilot in the Army National Guard. Dr. Shashy says to understand hearing loss, you first have to first know how hearing works.

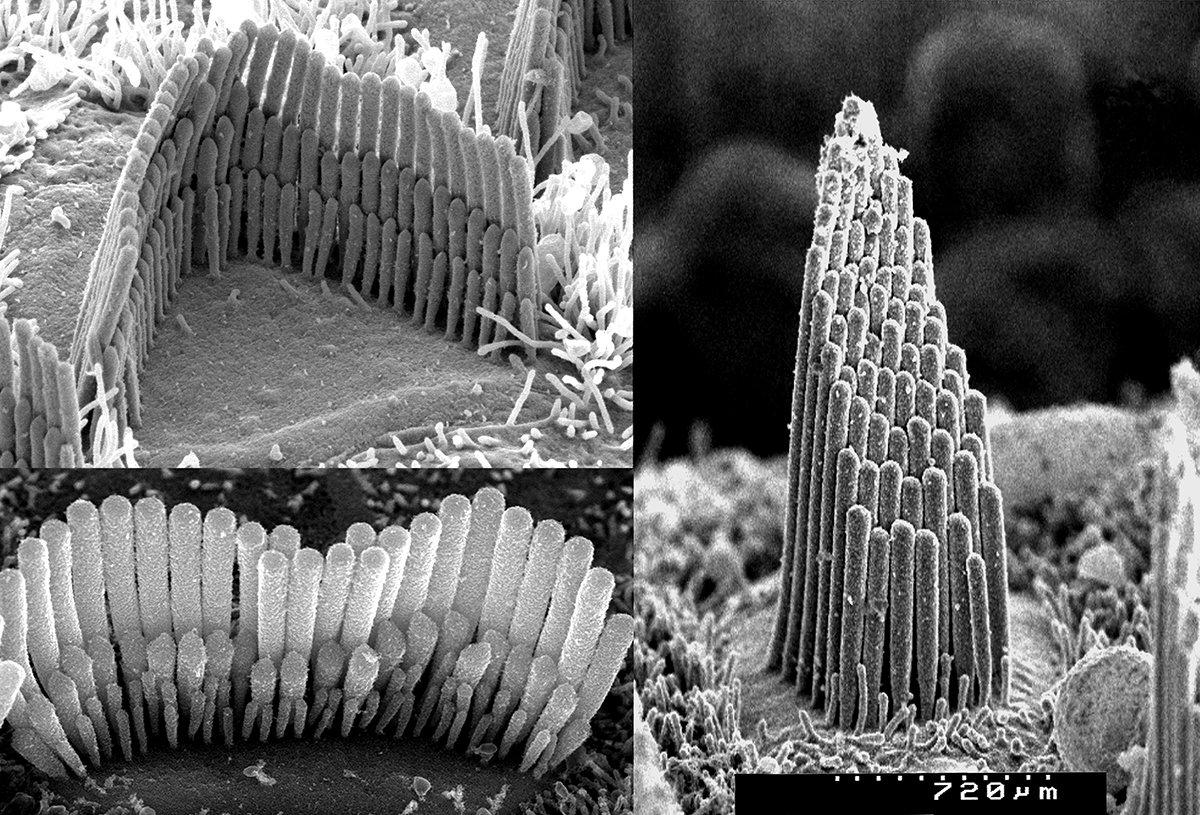

It starts with sound waves from a noise entering the outer ear. The energy from these waves enters the middle ear, where they vibrate against the eardrum. The vibrations from the eardrum transfer down small bones, known as ossicles, in the middle ear and then down into the inner ear. Once the sound vibrations work their way into the cavity known as the cochlea, they push against a bed of tiny hair cells that turn the vibrations into electrical impulses that travel along the auditory nerve to the brain, where they are recognized as sound.

Imagine that little bed of hair cells as a lush food plot, says Shashy. Now imagine a loud noise like a gunshot as a bucket of napalm someone drops onto that food plot. Instead of standing nice and upright like they are supposed to be, those cells are now laying there dead and are no longer able to function. Once those cells are dead, there is no way to get them back. When enough of the cells die, you start to lose your hearing.

Shashy says there isn't a good way to recover from hearing loss once it has happened — but preventing it is entirely possible. I have instilled into my kids that we don't go to the range without hearing protection. My choice for them is a pair of foam plugs under a set of earmuffs, says Shashy. I want them growing up thinking it is entirely normal, necessary even, to use hearing protection every time they fire a gun.

Field Protection

That double layer of protection is perfect for range time, but what about when you are hunting? That's where guys like Bill Dickinson come in. An Au.D. (doctor of audiology), Dickinson is also a lifelong hunter and shooter. After both teaching at the university level and working in the high-end hearing aid industry for years, Dickinson knew he could build better hearing protection for hunters. He started tinkering with hunting-style hearing enhancement and protection for his personal use. It worked, so he co-founded Tetra, which makes hearing enhancement and protection devices designed specifically for hunters and shooters.

When someone goes hunting, the listening experience is part of the overall enjoyment, Dickinson says. Yeah, you can protect your hearing with muffs or plugs like you would at the range, but then you can't hear a turkey gobble, an elk bugle, ducks coming in, the things you want to hear when hunting. Studies have found that 86% of hunters don't wear hearing protection because it decreases the general hearing experience of the hunt. For that reason, Tetra came up with an inside-the-ear electronic hearing protection device that can both enhance low-decibel sounds, like a buck walking through the woods, and shut down loud noises that might damage hearing.

(Stay warm and dry in the duck blind: Men's Insulated Max-5 Waterproof Parka)

It isn't just loud gunshots hunters need to be concerned with when it comes to hearing protection, Dickinson says. Let's stick with Dr. Shashy's food plot description of the inner ear. Imagine a game trail through the center of that plot, where deer and other animals walk across the same path every single day. That trail gets pretty worn out over time. The same thing happens to the hair cells inside your ear when you expose them to repetitive noises over and over. Say the sound of a mud motor, or duck calls in the blind. We did nine studies where we took OSHA approved sound measurement systems to the duck blind. In every case, the sound recorded exceeded OSHA recommended noise levels for an entire month in less than 45 minutes. Four of the nine hunts didn't even include a gunshot; it was just the general noise from motors, calls, and other parts of the hunt. Now imagine doing that to your ears day after day as the season wears on, and doing it year after year.

(Don't miss: Will Duck Hunters Be Able to Find Ammo This Fall?)

Even if many of those repetitive noises aren't as loud as gunshots, you can still lose the hearing that comes from that worn path through the hair cells. In real life, that translates to a loss of hearing in a certain frequency range. You might hear sounds above and below that frequency just fine — but if that range includes a turkey gobble or elk bugle, you lose out on a lot of what makes hunting enjoyable.

One of the early companies to realize the need for hearing protection tailored to the needs of hunters was Walker's Game Ear. In the late 1990s, the company released the original Walker's Game Ear. The muff-style hearing devices incorporated technology that amplified low-volume noises like a distant elk bugle but shut out loud noises like gunshots before they had time to reach the inner ear and cause damage. Hunters could protect their hearing in the field while still enjoying the sounds around them and participating in quiet conversation with hunting partners.

Over the years, the company refined its designs, making the muffs slimmer, lighter, and rechargeable, then, eventually, moved to earplug-style devices that could pick up sound direction and not get in the way when mounting a shotgun or rifle.

Soon, other companies like Axil also began tailoring hearing protection for hunters and shooters that enhanced their enjoyment of the sport while protecting their hearing. As the cost of these devices came down, more and more hunters made them a regular part of their outdoors gear.

You will absolutely never hear me say a bad thing about any of our competitors' hearing protection devices when it comes to protecting the ear. That's because I know that noise-induced hearing loss is 100% preventable, and any hearing protection during a hunt is better than none. First and foremost, hearing loss prevention is my main goal, and anything that works to that outcome is a good thing, Dickinson says.

When choosing a hearing protection system for hunting, Dickinson says finding something that enhances the hearing range you need, while at the same time dampening dangerous noise levels and still allowing you to pinpoint directional sounds, is crucial to an overall enjoyable experience.

Our brain recognizes sound direction by registering the speed and decibel level of the sound based on what direction it comes from, Dickinson says. The ear closest to the sound sends those sound waves to the brain faster and louder than the off-side ear. The sound takes a bit longer to travel around the head and is insulated a bit by hair as it gets to the off side. Our brains are able to process that minuscule difference to register sound direction.

Hearing devices that completely cover both ears can make it difficult for your brain to process sound direction. I experienced this firsthand last spring when I tried a pair of electronic sound-enhancing muffs during a turkey hunt. While I was able to hear turkey gobbles and other noises much better than without the muffs, I could not tell which direction the gobbles were coming from.

The loss of satisfying hunting opportunities and general lifestyle conditions that come with decreased hearing ability aren't the only things hunters and shooters should worry about when it comes to protecting their ears. Numerous studies have now shown that hearing loss from ages 35 to 50 is the No. 1 predictor of increased Alzheimer's disease and dementia risk later in life. Once your brain loses the stimulation that comes from these frequency ranges, the part of it that processes those sounds just starts to shut down. Think of it like a muscle that never gets used. Eventually that muscle just starts to atrophy, Dickinson says.

(Don't Miss: Maintenance Tips for Food Plot Equipment)

Shashy, Dickinson, and other hearing loss experts want to change the way hunters look at hearing protection.

Think of it like this, says Dickinson. Twenty or 30 years ago, almost no one used safety harnesses in treestands. You would even see hunters in magazines and early videos in a tree without a belt or harness. Now, just about everyone uses them and you never see a photo or video of a hunter without one. The overall attitude toward safety systems has changed to the point that seeing someone not using one now seems strange and out of place to most hunters. That is what we are trying to do with hearing protection and enhancement. We want to see that same general change in attitude to happen among all shooters and hunters.

No matter your age, now is the time to start protecting your hearing. Preventing deterioration of your hearing now will pay off down the road. If you are mentoring young hunters and shooters, instill good habits so that they will still be able to hear years from now. You'd probably never dream of letting a son, daughter, or young friend climb into a stand without a safety belt. We all need to start thinking of hearing protection in the same way.