Have You Ever Forged a Knife Before?

Next to your firearm or bow, a good knife might be the most important tool you take afield. A quality knife is more than a tool. It is the bridge between the taking of an animal and food on the table. A great knife feels alive in your hand, balanced, obedient, it becomes an extension of the hunter. If that knife is one forged by your own hand, it transcends mere function, it brings a personal touch to your hunt that a production knife just can't duplicate.

While the process is detailed, and it does require some relatively specialized tools, it's a project most outdoorsmen and women can tackle. Master knifemaker Chris Smith, of Chris Smith and Son's Custom Knives recently walked me through the process of turning a hunk of raw steel into a functioning blade.

Let's start with the tools. You will need a way to heat metal. The most popular forge styles are coal and gas. Coal forges get hotter than gas, sometimes hot enough to ruin your steel, and require more finesse and care to maintain a consistent temperature. The plus side to coal forges are their lower costs, and the ability to reach the higher temperatures needed for certain metals or blacksmithing techniques.

Gas forges are easier to use, maintain consistent temperatures, and are less likely to overheat your steel. While they can be more expensive up front, gas forges are the choice of many professional knife makers, including Smith. Gas forges are often smaller and more portable, running off grill-style propane tanks.

The next tools on the list are hammers and an anvil. Forging a knife means heating the steel to an almost molten point and hammering it into the shape you desire. Specialized forged blacksmithing hammers are nice, but a beginner can get by with small sledges ranging from 1 to 3 pounds from your local hardware store. Use flat-faced hammers for pounding steel flat, and cross peen hammers with a sharply angled face for stretching the metal. Anvils can be traditionally shaped, or something as simple as a short section of railroad track. Mount your anvil at a comfortable working height on a metal stand or a solid section of log. Whatever you mount the anvil on, make sure it is solid enough to withstand heavy hammer blows without moving.

A belt grinder with various grit sanding belts is used for shaping and polishing the blade. Other tools include a tank full of oil (common vegetable oil will work) for quenching the blade and hardening it. More on that later, though. A drill press makes attaching a handle to the knife to the tang easier. To move and hold your steel, a good set of blacksmith tongs are called for. You want to be able to grip the hot steel tightly and move it around on the anvil without dropping it.

Not certain you want to invest in all this equipment to build a knife? Check around social media for blacksmithing and forging groups in your area. Many hold blacksmithing hammer-ins on a regular basis, offering the chance to work on your knife under the supervision of experienced knife builders. Nothing on social media? Check with local horse clubs to see if they can recommend a blacksmith in your area.

Next on the list is suitable steel. Smith says you can find good knife steel in older American-made files and in older band or circular saw blades. Like the files, newer saw blades are often made with inferior steel with hardened teeth added later. Check antique or flea markets for files, or long-standing saw mills for blades. They often have worn-out blades lying around that they will sell for very little.

While old tool steel works, Smith recommends going with new steel for your knife. Metal dealers can often be found in larger cities and many mail order suppliers can be found online. Smith likes high-carbon 1080 or 1084 steel for knife making. Other popular choices include 1095, W1, O1, 52100 or W2 steel. All should be available from most steel suppliers.

Once you have steel and the tools to work it, its time to forge a knife. Smith starts by heating the steel blank in his forge until it reaches 1600-1800 degrees Fahrenheit.

I go by color as much as anything, Smith said. You are looking for a nice, bright orange.

When your steel reaches the right temperature, begin roughly shaping the blade with a hammer. With just a few strikes of his hammer, Smith had a rough blade design. He pointed out the curve of the blade and the tip and explained that, as he hammered and tapered the blade shape, the metal would actually stretch, and the point would migrate over the opposite side of the blade.

It's called distal taper, the steel stretches and moves as the blade lengthens and tapers, Smith said. The technique gives you the best blade profile.

Once you lose the color in the blade, quit hammering, Smith said. You are wasting time and energy. Just move it back to the forge and heat it back up.

After multiple trips to the forge, Smith had a nearly finished blade. As he pounded the steel, black flakes of scale would form on the blade.

It's oxidation, almost like rust. The hotter the metal, the faster it forms, Smith said.

He recommends keeping the scale scraped off your anvil as you work to prevent the scale from contacting the surface of the steel.

Satisfied with his blade, Smith moves from the anvil to the grinder. He starts with a coarse belt, 36 grit, to shape the blade and smooth the surface.

At this point, check repeatedly to make sure your blade edge is aligned down the center of the spine, it's easy to get it off one way or the other with the grinder, Smith said.

Smith continues grinding and polishing, switching next to a 60-grit belt, then a 120-grit, finer version. When he finishes with the third belt, the blade looks finished. The previously dull steel is now shiny ‚ the shape perfect. I enquired as to what would happen if you tried to use it at this point. You could, but it wouldn't be a good knife, it wouldn't hold an edge and would probably shatter the first time you tried to use it, replied Smith.

From there, the knife moves to the drill press where holes are drilled through the tang for later handle attachment.

You want to do this step now, Smith said. Later the steel will be so hard that you will wear out your drill bit.

To transform the blade from the raw state into a working knife, the next, and perhaps most important steps in the process, are the normalizing, hardening and tempering of the blade. Normalizing the steel is accomplished by heating the knife evenly to at least 1,600 degrees. At this point, the steel no longer sticks to a strong magnet Smith keeps mounted below his forge. The steel is then allowed to cool and heated again to a slightly lower temperature, around 1,500 degrees. The knife is cooled again and then heated a third time to 1,400 degrees. This process equalizes the steel, aligning and evening its molecules.

The raw steel has carbon and iron molecules, Smith said. To harden the blade, it goes back into the forge to heat above critical temp, meaning the iron won't stick to a magnet. You heat the steel to that point, then immediately plunge it into oil to cool the blade. The heating of the steel forces the carbon molecules into the iron molecules. When you quench it in oil, the rapid cooling locks those molecules together, making the steel stronger than it was while raw.

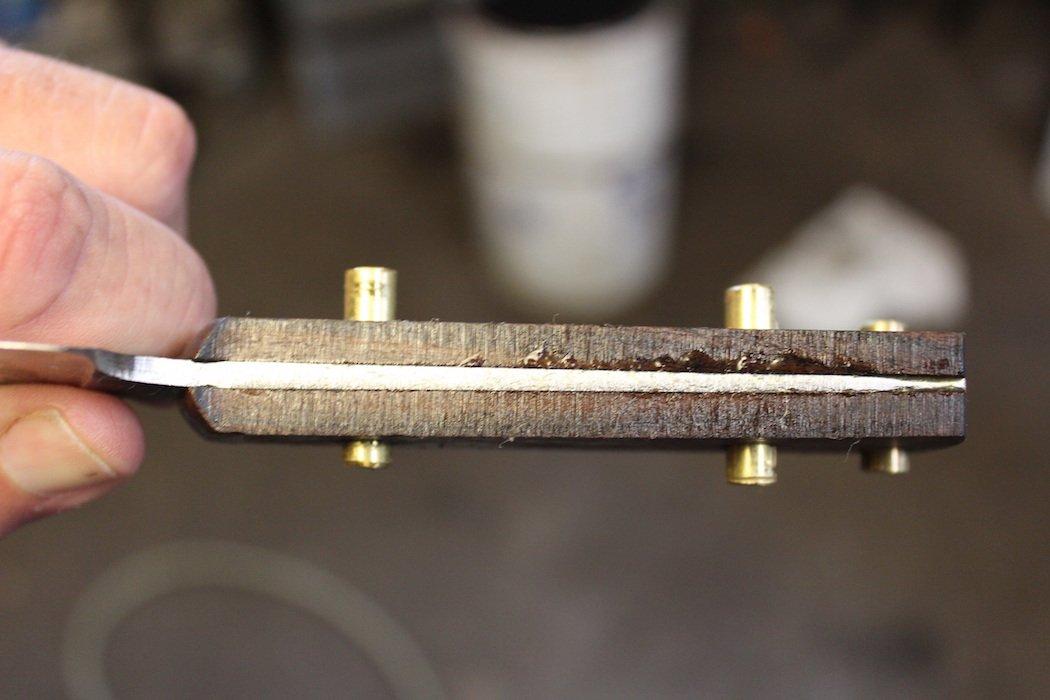

Chris uses a custom oil designed for metal working in his quench tank but said that common vegetable oil from the grocery works well. After quenching, he tests the hardness of the blade by running a file across the metal.

You want the blade to be hard enough that the file doesn't dig into the metal, Smith said. You can temper several times and not hurt the blade. A lot of knifemakers temper at least twice on every blade.

After the second quench, the blade passed the file test. Next comes the tempering of the blade. After the quench, the metal is hard, but brittle. Tempering heats the blade to around 450 degrees and holds it there for at least an hour. The tempering process slightly reduces hardness of the blade, but also toughens it and makes it less brittle. If you live alone, or have a very understanding wife, you can temper your blade in your kitchen oven. Smith uses a small toaster oven in his shop.

In a pinch, it even makes a mean Hot Pocket, Smith joked.

Once the knife comes through the tempering process, it's back to the belt sander to dress and polish the blade again. Continue working through finer and finer grit belts until the blade is dressed and the edge is shaving sharp.

When it comes to attaching handle scales, Smith prefers a combination of two-part epoxy. He uses West System Marine Epoxy and pins the traverse (both handle scales and the knife tang), passing through the holes drilled in an earlier step.

The epoxy needs 12 hours to cure, so I glue them on first and let it set, then install the pins afterward, Smith said.

The handle scales go on oversized. Then the final shape is achieved through more time at the belt grinder.

Once your grip is shaped to your liking, protect the handle with oil or polyurethane if desired. The final step in forging your own hunting knife is the final sharpening to a razor edge.

A thing of beauty. A work of art. This knife is the result of a labor of skill and hard work. But it's well worth it. And hopefully the deer seasons to come will keep it crimson each fall.

Don't Miss: 20 Tips for Blood Trailing Deer

Are you a deer hunter wanting to learn how to accomplish your goals? Check out our stories, videos and hard-hitting how-to's on deer hunting.