The new RT-QuIC test could be a faster, more effective way to test for the disease, but there are hurdles to cross first

Chronic wasting disease is one of the foremost challenges faced by today's deer biologists and managers. Researchers are fighting many battles in the war against this threat, and one of the biggest is the inability to efficiently test live animals for CWD.

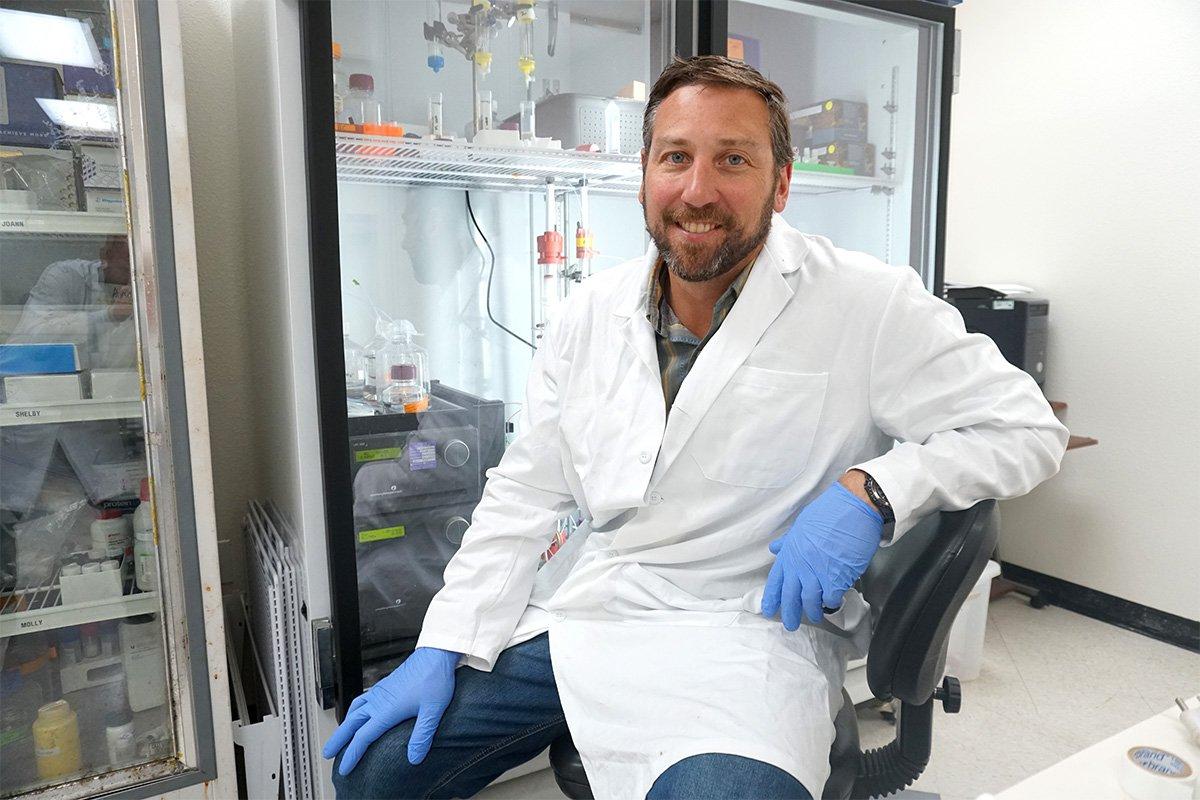

Davin Henderson, a protein chemist and founder of CWD Evolution, is developing a new test that aims to address that issue. His company recently received a grant of nearly $200,000 from the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture to focus on detecting CWD with his real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC) test. Unfortunately, disbursement is on hold indefinitely due to COVID-19.

Enhancing Pre-Existing Technology

Prions are malformed proteins that cause certain diseases, like CWD, and researchers still know little about them. But increased prion-testing capabilities are a step in the right direction. Henderson and his colleagues at Colorado State University have been using RT-QuIC to test live animals for about seven years. Now Henderson is working to make this test more efficient, which would help increase the frequency and geographic scope of testing. More (and better) geographical data is crucial to understanding - and overcoming - CWD.

How the Test Works

The USDA-approved tests currently on the market aren't sensitive enough to use on live animals, according to Henderson. Researchers need a better test to analyze tissue from live cervids. He says tonsil biopsies work best for testing live animals, but those tissue samples are difficult to take without special tools, which can't be reused without fear of animal-to-animal contamination. His team settled on a rectal biopsy instead, taking a piece of lymph node that accumulates CWD fairly early in the disease cycle.

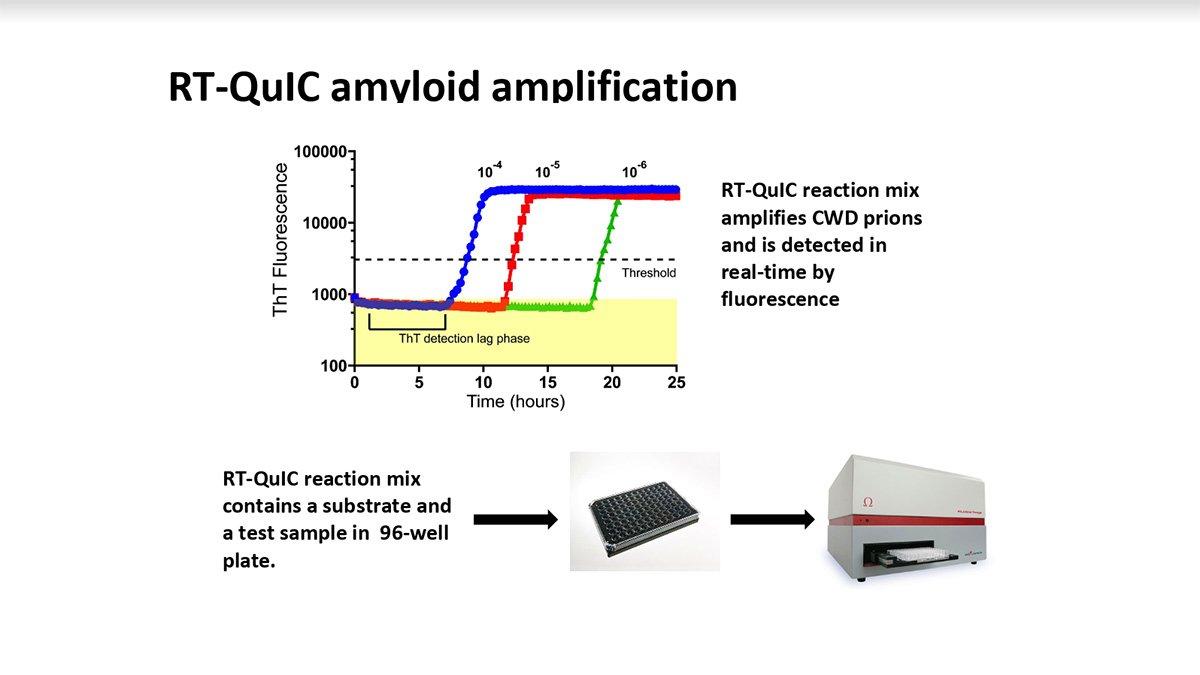

Once Henderson has that tissue sample, he's able to use his test. Instead of directly detecting the presence of CWD, his test amplifies CWD from very low, undetectable levels to something we can see with a fluorescent-based dye. Increased sensitivity is necessary in a live-animal test because the accessible tissue on a living deer or elk holds fewer CWD prions compared to the tissue you collect from a dead animal.

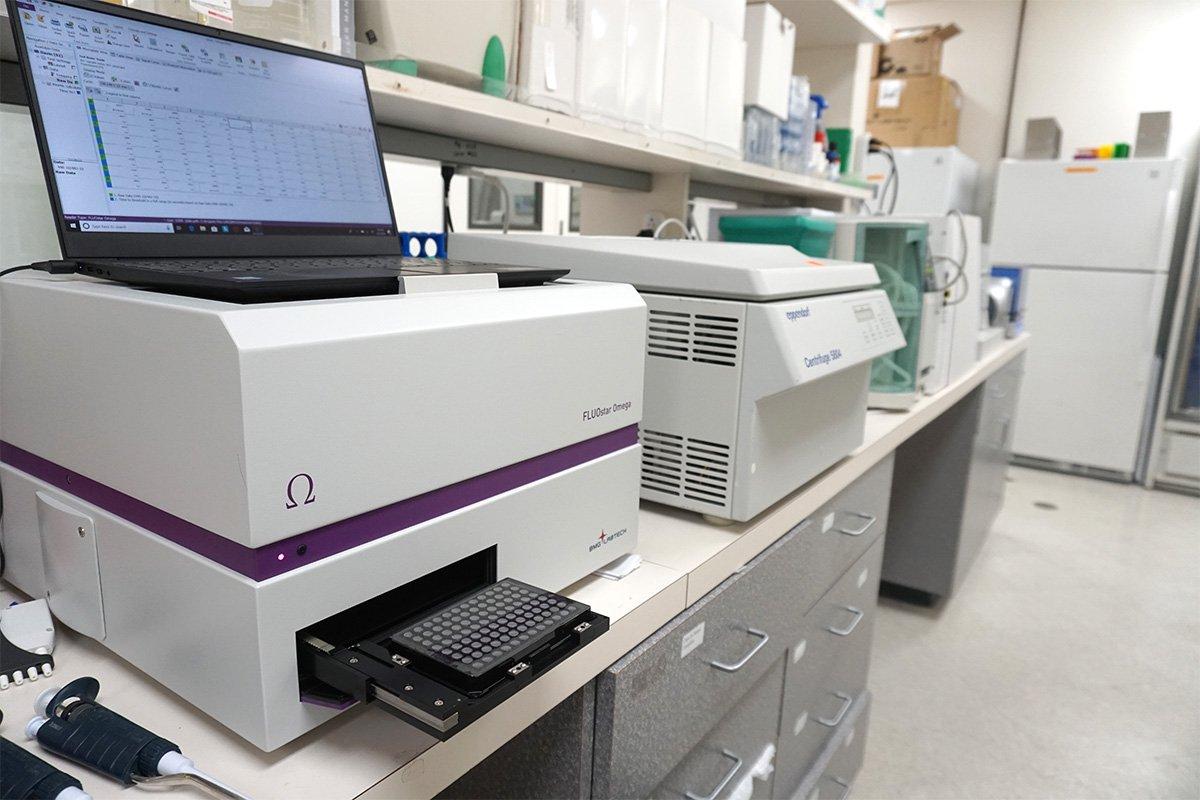

The major component of an RT-QuIC test is the reaction mixture, Henderson says. [It contains a] prion that is available to convert more prion proteins. That's what they do. They replicate themselves. RT-QuIC is a miniature replication, just like it would happen in the brain. If there is a prion present, it'll amplify it into more prions, but if there's no prion present, it won't amplify.

So how effective is this test?

We've gotten to where we're about 80 to 85% [better] at detecting CWD compared to the postmortem analysis, he says. To catch 85 to 90% of the animals that have CWD while they're still alive is pretty good.

That's the basis of his grant project. Henderson's goal is to refine the last few things that need to be done with this RT-QuIC test before he can submit it to the USDA for approval, and widespread use. So, while Henderson can see the finish line, there are still some hurdles to cross — the final research stages, and the approval process — before rolling out this test to diagnostic labs.

I want to take these tests and get them out there in the real world where they can do good at a larger scale, Henderson says. We have a ton of data on how well this test works for both live animals and postmortem tissue. It's easy, fast and more than 10,000-fold more sensitive than currently available CWD tests. I'm really hoping the USDA makes this a priority. I think the more people that are asking for it, and the more people that are aware there's a possibility for this type of testing, the more inclined they'll be to take a good look at this.

What Live Testing Means for Hunters

If Henderson's test passes USDA clearance and works as advertised, it would solve quite a few of the problems we're facing in the fight against CWD, both for captive and wild deer populations.

All deer breeders would benefit from this test, but certain cervid farmers would see an extra benefit. Some deer and elk have a genetic marker that makes them more resistant to CWD. In those animals, Henderson says, fewer prions accumulate during the early stages. This test would theoretically improve accurate testing in CWD-resistant deer and elk.

This new test would also help wildlife agencies manage wild cervids, too. Increased testing supplies more data for analysis, which provides a better understanding of the disease's prevalence.

This test has the capacity to be very sensitive and applicable to a large series of samples, Henderson says. If wildlife agencies or DNRs wanted to use this testing for surveying, they could learn a lot more about the samples they have. This would also enable a capture-and-recapture study to look at certain deer over time by using radio collars.

It also allows agencies extra peace of mind when they have to transport live cervids. I support developing a more accurate and efficient live-animal test, says QDMA biologist Kip Adams. Anything that can help detect CWD in a live animal will help slow the spread of the disease, as CWD-positive animals could be better identified and thus not moved to a new location."

There are a number of states that import elk and move different species around to establish new populations, Henderson says. This type of testing could give agencies a safeguard that determines if there is CWD in those animals.

Finally, this test works just fine on dead deer, too. It would make life easier for deer hunters. Henderson says one of the major problems hunters face is the inability to test their own animals for CWD, and he believes this is the sort of technology that would allow hunters to take samples themselves and send them in.

I'm in the process of getting a test to market that will hopefully increase the speed in test results, as well as participation, Henderson says. I really think that if there was an easier, faster test for CWD, we wouldn't see such a large drop in hunter participation in areas where CWD is present.