It might be time to make some much-needed repairs

I once lived in a fantasy world where every bow was tunable, and it was my fault if it shot poorly. That's just not true. For some bows, no matter how I turn the arrow's nock, move the rest, tweak the cam timing, grip the riser or slide the nock point, I can't tune them.

It finally clicked when I spoke with Steve Johnson, owner of Spot-Hogg Archery and maker of the Hooter Shooter archery machine. Using these, Johnson does extensive testing on bows to determine why some are tuned more easily and shoot more accurately than others. What he learned will change the way you look at the bow-tuning and buying processes.

Diagnosing a Lemon

I've shot bows so out of tune that I could see the arrow's fletching slashing left and right just as it departed the bow. When paper tuning, you're not only fighting the effects of the sideways movement of the string but also the effects of the inevitable contact between fletching and the rest.

According to Johnson, this problem is most often caused by a change in cam tilt. Of course, when you release the string, the cam goes back to the way it was before drawing it. That means the string must move sideways as it travels forward. The arrow's nock has no choice but to follow the string and fishtails sideways as it leaves the bow.

All of this can be the result of axle holes that aren't square with the limbs, cam bushings that are worn, or improperly spaced cams within the limb forks. It can also result from a split yoke harness that isn't balanced correctly.

With single-cam bows, there is much less control over vertical nock travel because there is no actual timing change. If the cam is well-designed, and the string and buss cable are the correct length, the nock point should be level enough to create good vertical arrow flight. However, the problem of cam tilt still exists, meaning that sideways string travel is just as much a problem with single-cam bows as with dual-cam models.

Avoiding a Lemon

Johnson has a systematic way to evaluate the cam lean on his personal bows using his shooting machine. Any pro shop that uses one of his Hooter Shooters (there are thousands in pro shops nationwide), should be able to perform this same test.

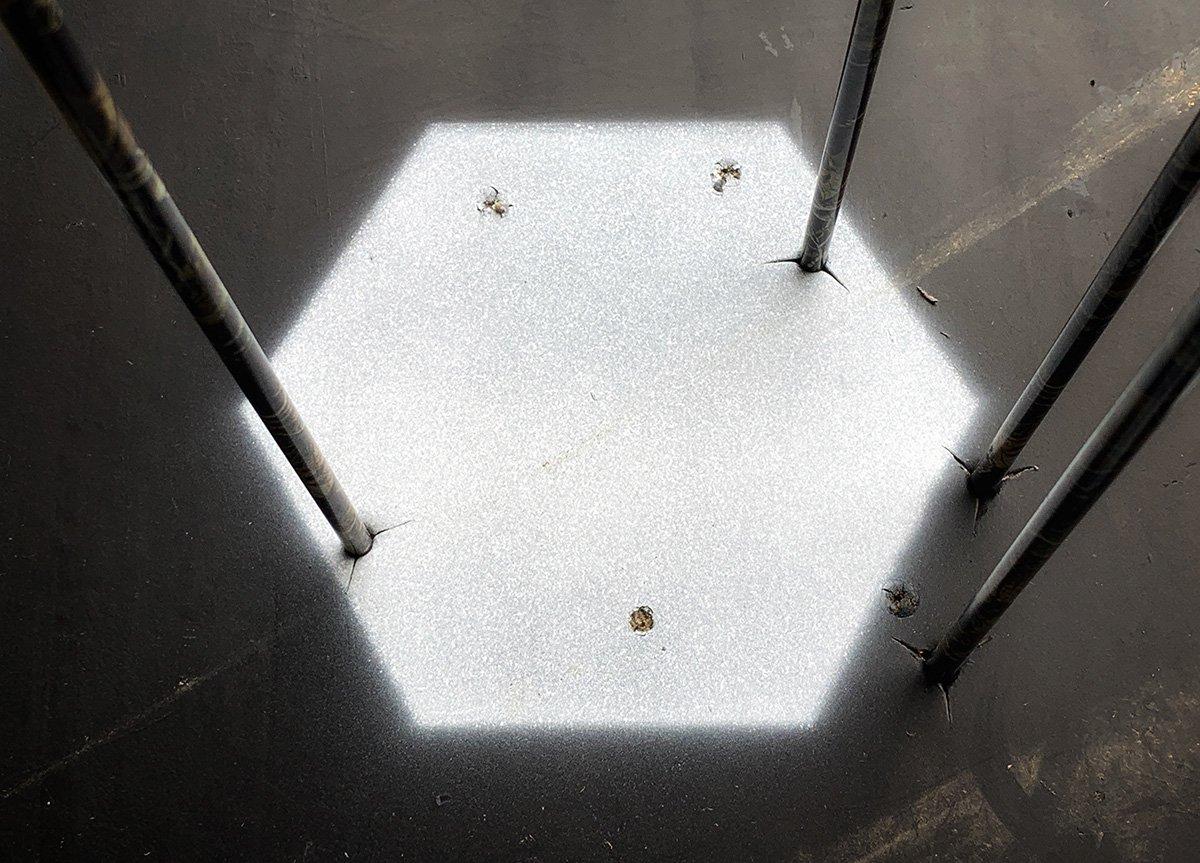

A small laser is placed against the cam that projects a dot from the top cam to the bottom limb and from the bottom cam to the top limb, both at brace and at full draw. In this way, he can tell how much the cam tilts and changes as the bow is drawn. He says his sweetest-shooting bows have a change in laser dot movement of a half-inch or less for each cam.

This often gets too technical for the average guy buying a bow. For them, I propose a simple visual test and then a tuning test in the archery shop. First, look down the string while holding the bow on the end. The string and the cams should all line up. If they are off before the bow is even drawn, you can be sure the cam(s) will lean more when you actually drawn back.

If things look good, ask the shop owner to paper tune the bow before buying it. If you're serious and have the money ready to spend, most of them will help. If he or she doesn't have time, ask if you can return the bow for a full refund if it won't tune once you get it home. In my experience, a well-built, properly set-up bow will tune on the first arrow most of the time.

Fixing a Lemon

Let's suppose you already own an untunable bow. I don't know of a single bow company that will replace it as part of a warranty program. So, you can pawn it off on your least favorite brother-in-law, just stick it in the closet, or attempt to fix it.

Let's start with a two-cam or hybrid-cam bow. You can change the vertical movement of the nocking point by simply changing the timing of the cams, but there is little most bowhunters - even good bow mechanics - can do with a bow that has a string slicing left or right.

Shooting through paper as you try different remedies is one way to gauge success, but Johnson's laser idea is a real time saver. It isn't hard to set up if you can get your hands on a laser pointer and a shooting machine. Again, check the amount of cam tilt at brace and full draw and see what reduces the amount of lean.

Most experience best results by observing three things: the harness system, bushings in cams and the cam spacing on the axle. As previously mentioned, axle holes can be a problem if they aren't square to the limbs. Other than buying new limbs, there isn't much you can do to fix this. (Johnson sells a gauge that checks axle holes.)

The split-yoke harness system on many bows stabilizes the limb tip(s) and helps reduce cam tilt. You can adjust a split harness — whether on a two-cam bow, a hybrid cam bow, or on the idler wheel of a single-cam bow — by shortening one side or the other by twisting it. This slightly torques the limb tip. Of course, the idea is to twist it into a position where the cam is in line with the string.

Older bows used cam bushings to reduce friction with the axle. These bushings eventually wear out, and as that happens, cams lean more. Determine if this is a problem by putting the bow in a press. With the tension off the cams, try to wobble them back and forth. Ideally, they won't budge, but if they wobble more than a slight amount, it's likely from worn bushings. Most archery shops can replace them.

Finally, you can change the cam spacing on the axle. This step is more difficult than other solutions, so save it for last. It requires completely removing the axle and experimenting with the orientation of the thin spacers that position the cam in the limb fork. Not all bows even have these spacers, so it might be a moot point. This can be tedious work, but it can pay off.

Finally, don't immediately assume all sideways paper tears are the fault of the bow. One cause of sideways paper tears is a draw length that's too long. Also, slight grip changes and arrow nock rotations can solve this problem. Exhaust every normal tuning procedure before beginning massive surgery on a bow.

Don't Miss: How to Shoot a Bow

Check out more stories, videos and educational how-to's on bowhunting.