Research shows that switching from corn to milo or grain sorghum could reduce aflatoxin rates and predator densities

Turkeys have been taking it on the chin. Populations have fallen, especially in Southeastern states. According to many top turkey researchers, the reasons are many, including habitat loss, nest predation, and disease, among others.

Two of those issues can be directly related to something that many hunters do on a regular basis — feeding corn for deer. The first problem for wild turkeys when it comes to corn is aflatoxin. These are toxic chemicals produced by a species of fungus in the Aspergillus genus that grows on the corn itself. Aflatoxin rates as low as 200 parts per billion (ppb) can harm game birds, and turkey poults in particular, by causing liver dysfunction and immunosuppression.

Natural build up of aflatoxin on bait corn can be harmful or even fatal to wild turkeys. ImageBy-valleyboi63-turkey-feed

The fungus grows fast under warm, damp conditions, which often occur just when hunters have corn lying on the ground in late summer or early fall. It can grow quickly. A recent study by the MSU (Mississippi State University) Deer Lab monitored corn piles placed on the ground during the summer and fall, the very times when young turkeys are out foraging to put on weight for the upcoming winter. All the piles tested negative for aflatoxin the first three days on the ground. But by the fifth day, nearly half the piles tested positive at an average concentration of 400 ppb. By days eight, nine, and 10, all of the piles tested positive with rates as high as 2,000 ppb, 10 times the rate that can harm poults. Since falling poult numbers per hen is one of the chief reasons for reduced populations, anything that might be negatively affecting poult health is concerning.

The next issue with corn is nest predation. Anyone who feeds corn knows that it attracts nest predators like raccoons in large numbers. Many hunters report trail camera photos of 15-20 raccoons on a regular basis. That’s a lot of predatory animals shuffling around looking for something to eat. Even when the bait is not longer in use, many of these animals stay in close proximity. That means that they are still around and looking for a meal in the springtime, and turkey nests are often the unlucky recipient of that attention.

So what’s the hunter who wants to feed corn for deer hunting or trail cameras but also wants to protect turkeys to do? Recent research from Oklahoma State University might have discovered an option. Switching from corn to milo, or grain sorghum, greatly reduced non-target species (raccoons) while maintaining a similar rate of feeding by deer.

Switching to grain sorghum (milo) as bait seems to be just as attractive to deer while reducing both aflatoxin poisoning and nest predator concentration. Image by Michael Pendley

Dr. Dwayne Elmore, Extension Wildlife Specialist for the Department of Natural Resource Ecology and Management at Oklahoma State University offers some insight. “The data was collected on Oklahoma State University property associated with deer monitoring. Specifically, we were conducting annual deer camera surveys on an approximately 1,000-acre property. I was working with the station superintendent to carry out these surveys to determine deer density, sex ratio, and doe:fawn ratios primarily. We were generally following the Jacobson method of using baited infrared triggered cameras (ITC) to provide the property with management guidance. We were using one camera per 100 acres, and the locations were systematically distributed across the area. We pre-baited the camera traps with whole corn for 10-14 days and then ran the cameras for 10-14 days [depending on the year]. One year, we could not get whole corn, so we used milo, or grain sorghum. When going through the data, it was clear that the mammalian non-target images were dramatically lower, which meant not only could we analyze the camera data faster, but we used less bait.”

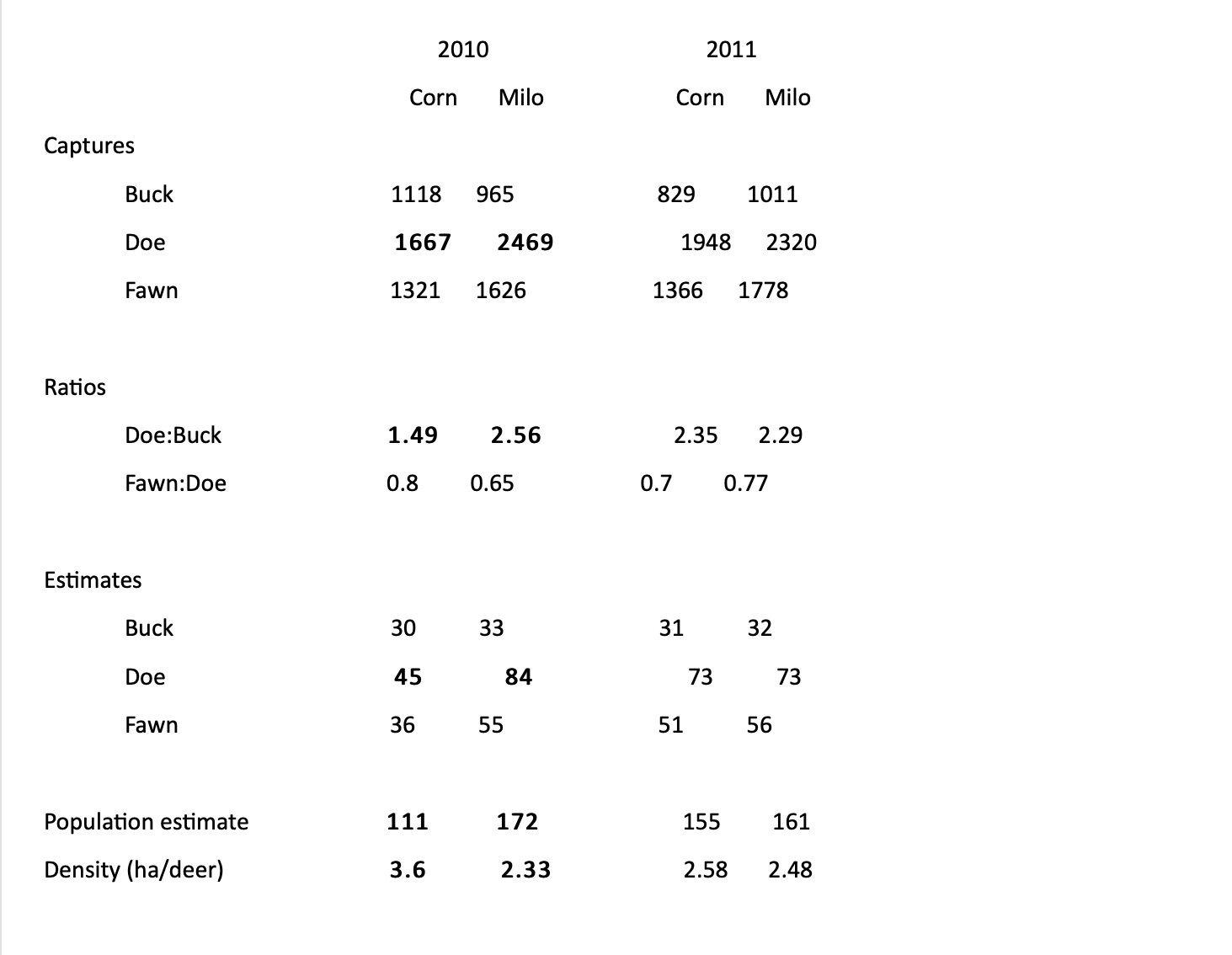

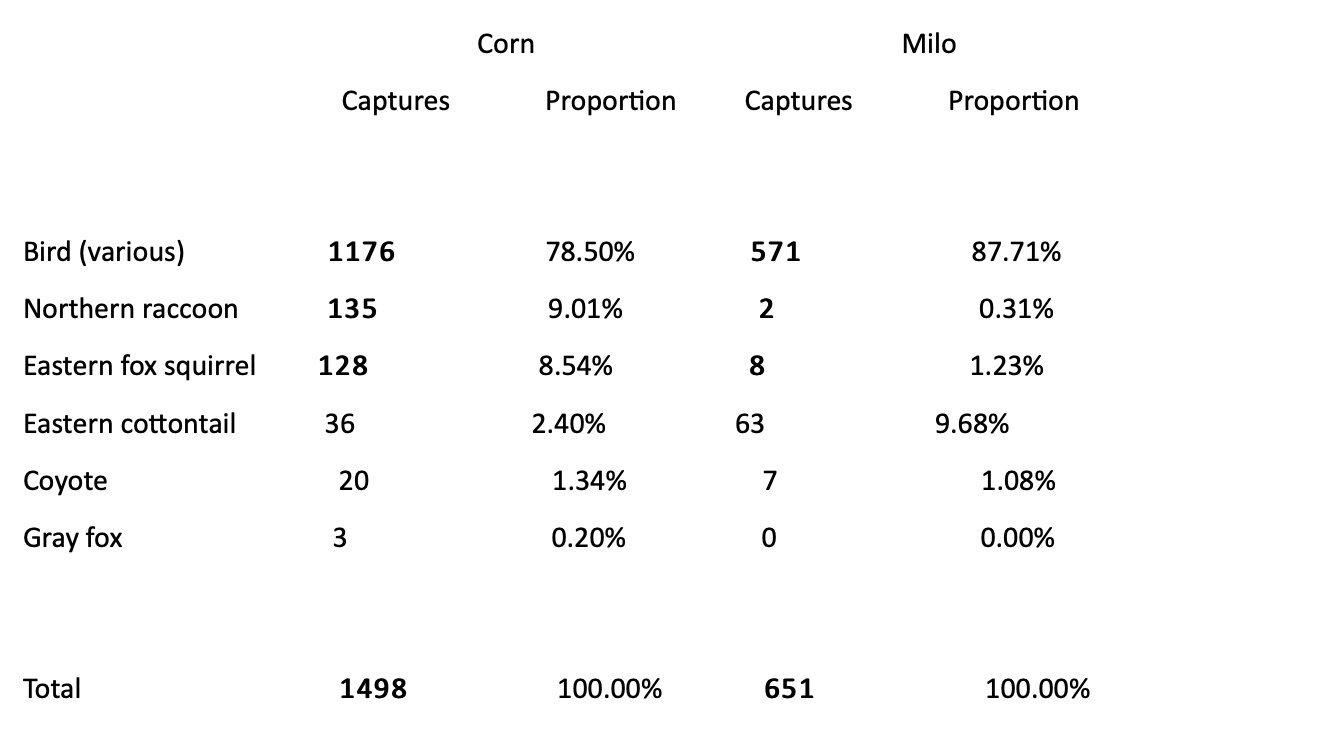

Elmore continued, “So, we decided to test this a little more formally. We randomly assigned half the cameras to corn and half to milo the following year using the same protocol we had previously been using, except that we doubled cameras such that within every 100 acres, there was one camera with corn and one with milo. We did this for two years and bait was randomly assigned to each year to each camera trap site. The tables below highlight the results. The first table is the deer data and the second is the non-target data.”

Milo vs corn deer use chart image by Oklahoma State University

As you can see from the tables above, deer use for corn and milo stayed consistent. Both bucks and does hit both baits on a regular basis. But notice the second line on the non-target chart below. For raccoons, photo captures went from 135 for corn to just two for the milo. Photos of both coyotes and gray fox also dropped on the milo baited sites.

Milo vs Corn non-target animal chart. Image by Okalahoma State University

As an added bonus, Dr. Elmore also reports that aflatoxin growth on milo is lower than on corn. Aflatoxin production occurs when the Aspergillus fungus has access to the sugar present in grains. Feeding grains with lower available sugar, such as milo, reduces the chances that aflatoxin will be present at the time of purchase and results in a slower growth rate while in use.

Dr. Elmore offers these takeaways from the research:

Milo (grain sorghum) can be attractive to deer, at least in some areas. Familiarity with a food and overall food availability can certainly change palatability (what is attractive as forage), so there’s no guarantee every place would see the same result. However, if a landowner is primarily using the grain to feed deer, attract deer, or just see what bucks are available, milo may be a viable substitute to corn.

Population estimates were dramatically different between bait types in one of the two years. Milo was similar between years, corn was not. So, comparisons between corn and milo between years or between properties should be viewed with extreme caution. Landowners should be consistent if using bait to estimated doe:buck ratios or to estimate abundance or density and realize that subtle changes in protocol can skew estimates.

Milo dramatically lowered non-target use. This has multiple benefits, including less grain used and not supplementing mesocarnivores, which prey upon ground nesting birds such as wild turkeys. Other research has shown that large portions of supplemental grain is being consumed by non-targets.

Cost Comparison

While prices will vary from state to state depending upon availability and popularity, I checked several feed stores in Kentucky, Tennessee, and Indiana. Most carried or could get feed sorghum (milo). The prices ranged from about a third higher than corn to about double. At the feed store nearest my house, corn was $9 per 50 pounds and milo was running $18.50 per 50 pound bag. While that might seem cost prohibitive at first glance, ask yourself how much of that corn is going to non-target animals like raccoons and opossums. Take those out of the equation and the price gets much closer, possibly offering an even better value.

Will My Deer Eat It?

Whitetails are creatures of habit. Just like with any new food plot or feed, it might take a while for them to figure things out. In ag areas where milo is grown on a large scale, deer are probably already consuming it on a regular basis. In areas where it isn’t commonplace, mixing milo with corn is a good way to introduce the feed to deer in the area. Once they key in on milo as a food, they will consume it consistently.

Will switching from corn to milo feeding be the magic bullet that restores turkey populations back to the glory days of the ‘80s and ‘90s? Probably not. But reducing predator loads in nesting areas and aflatoxin poisoning in poults certainly can’t hurt.