A story on living life, raising kids, and handfishing for flatheads

At one in the morning I knocked on the door of our single-bedroom apartment hard enough to wake my wife, Michelle. I needed her to unlock it. She answered with a .44 Special revolver at her side and demanded to know why I'd made such a racket in the hallway at that hour. My hands were so cut and skinned from the jaws of a flathead catfish, I explained, that I couldn't stand to stick them in my pocket to look for my keys. I showed her my knuckles: peeled, blistered, and oozing.

Heaven help, she said. Or probably something worse. That's from a fish bite?

Yes, I said. And I think our lives are about to change.

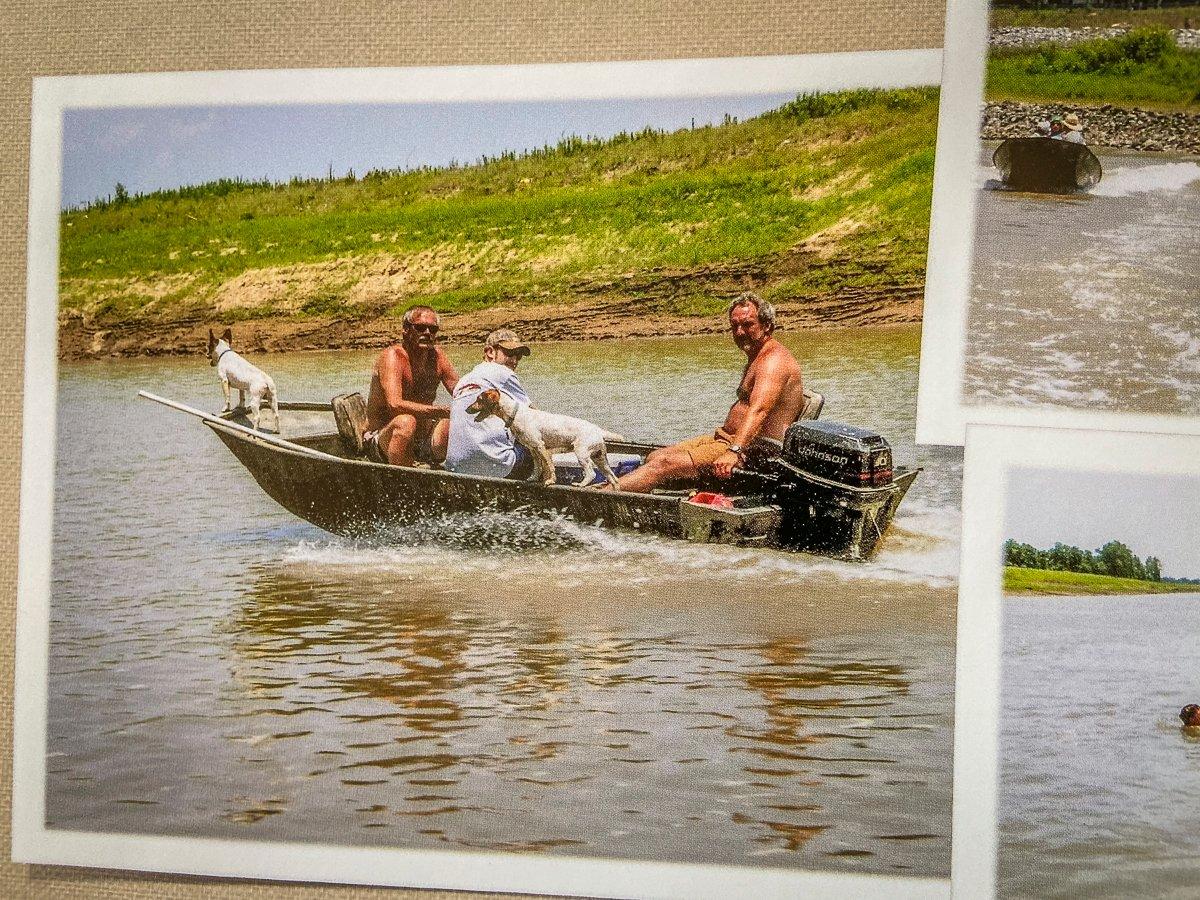

It was 2005, and we'd been married a month. Earlier that week I'd hit the road for my first field assignment for an outdoor magazine. I was to go to Mississippi, noodle a catfish, and write a story about it. My host was a hard-boiled Mississippian named Bob, along with three johnboats full of his buddies, all sunbaked, middle-aged, and smiling. At the time I was 21 and green, and impressive to no one.

Bob was a man of upper body strength and careful diction. When he didn't dismiss my presence altogether, he taunted me with names like Junior and Yankee because I'd shown up and said, first thing, that I was there to go noodling. Mississippians simply call it handfishing. Later, as we were prepping boats at the ramp, I told Bob I was planning to wear leather gloves. He stared at me in silence, and it felt as though his gaze might cause my skull to split, allowing the terror I held inside to run out into the mud, where everyone could see it.

No, you ain't wearing gloves, he said.

Then he grabbed me by the back of my shirt, picked me up off the ground, and feigned as if he were going to toss me into the Yazoo River. His buddies howled with laughter. He set me down, laughing himself, and said, It don't matter I guess, because you gone get too scared away.

No, you ain't wearing gloves, he said.

It was said that Bob could hold his breath for two minutes at a time and catch two catfish in one dive, threading his arm through the gills of one, and hanging on to the jaw of the next one. And Bob was so skilled that he could do it all barehanded, without so much as a scratch to show for it, even though his forearms were laced with catfishing scars.

I fished without a glove like Bob said I was going to do. The flathead I caught shook its jaws across my knuckles and fingers and palms, and I could feel the skin shearing away as it did. But I held on and threw the fish into the nearest boat, with Mississippians cheering me on, drunk on the violence like Romans in the Colosseum. I shook Bob's hand and asked for a beer. Bob didn't drink anything harder than grape soda himself — but one of his buddies tossed me a Busch Lite.

Bob looked at me, cocked a corner jaw grin and said, You all right, Junior.

I never saw him again. About a year later, before my story was published, Bob was killed in a farming accident.

Learning the Craft

That Mississippi flathead's bite had gone more than skin deep, figuratively speaking anyway. All that following winter, I talked about grabbing catfish. My buddies and I would be sitting in layout blinds on mud flats, waiting for gadwalls, and I'd point out a hole in a cypress stump and declare that it'd be a good spot for a cat.

I drove them nuts, Michelle too, but there were flatheads in the rivers and lakes around home, and I wanted to learn to grab them. My mother-in-law — a world-class junk peddler — had a collection of plastic 55-gallon barrels in storage that she'd been saving for something special. She cut flathead-sized holes into them and gifted them to me. On a February day in a sideways snow, my buddy Tim and I pulled on waders, took the barrels, and anchored them to the riverbank. I worked with a purpose and Tim helped, but only because it was February and he had nothing better to do. When the water got high enough, I reasoned, catfish would get into them to spawn, and they'd be good spots to go noodling.

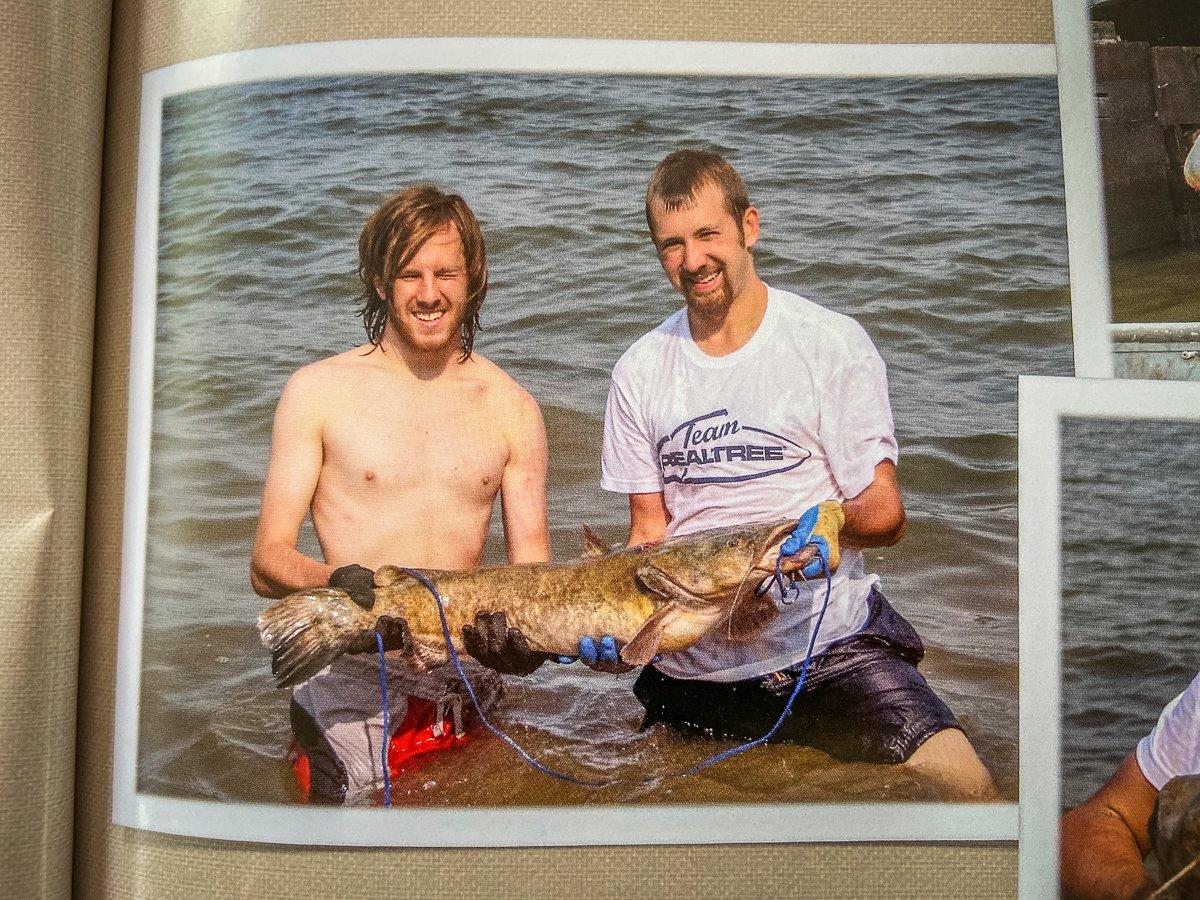

The barrels all washed away except for one, and that following June I wrestled a 16-pound flathead out of it, barehanded again, and slung it over the gunwale of my johnboat, where it flopped and thrashed at Michelle's feet. Tim was in his boat, watching the whole thing. None of us had ever caught a flathead that big on a rod and reel; it was a fish that when fried up, belly and cheek meat included, fed six people.

A few days later, we caught a flathead that bottomed out a 50-pound scale.

(Rod and reel more your style? Check out the 5 Top Lures for Summertime Bass Fishing)

Hitting It Big

When I was a kid, noodling was an underground style of fishing practiced only on the fringes. First time I saw it, I was watching weekend outdoor television — there was no Outdoor Channel then — and Wade Bourne's show Southern Outdoors had a spot about handfishing in Mississippi. I didn't know it at the time, but I'd get to know Wade a few years later, and he put me in touch with those same guys he fished with for my story. Bob was their ringleader.

By then, noodling was better known — and even becoming a part of pop culture, thanks to the 2001 release of Okie Noodling, an hourlong documentary that profiled legendary handfishermen like Lee McFarland against the backdrop of the Okie Noodling catfish tournament — an event that still goes on today. Okie Noodling is 20 years old now but as captivating to watch today as it was then.

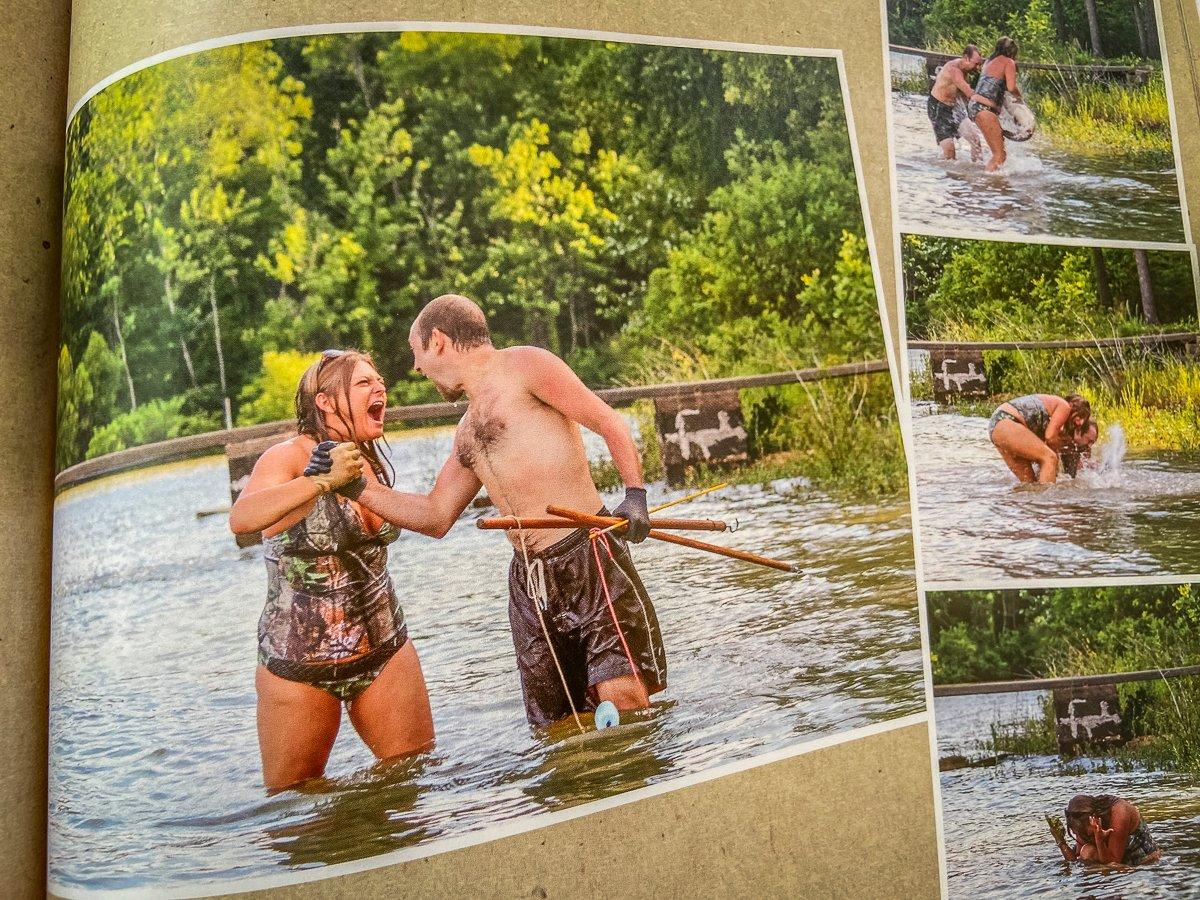

We spent Junes and Julys through the late 2000s probing for holes along rocky shorelines with our feet, and daring one another to reach in first to see if something was inside and willing to bite an intrepid hand. We'd party at night after noodling all day, soaking catfish wounds with peroxide and whiskey, and listening to Pantera.

Michelle once said, Who needs tattoos when you got real scars?

***

(Classy enough for catfish noodling: Realtree Original 6-pocket Cargo Shorts)

***

I took a job in Memphis, and Michelle and I lived there two years, long enough to know we're not city people. One afternoon I could stand it no more, and so I quit my job, and on a whim, we decided to get in the car and drive east, to Watts Bar Lake. There, we met up with the Catfish Grabblers, Marty and Fostana Jenkins, who could be described as the Instafamous noodlers of the day, before there was Instagram. The Jenkinses worked in a candy factory, but on the side they filmed and produced catfish noodling videos. Their two most popular, Girls Gone Grabblin' and Girls Gone Grabblin' 2, were sold at Bass Pro Shops. Suggestive title aside, they were family-friendly and fun to watch.

It was cold and rainy during our visit, but the Catfish Grabblers took Michelle and me out for a tour; we caught some flatheads and talked ideas. Noodling mesmerized people — those were the words Wade Bourne had used when I'd asked him about it years earlier — and as a young writer, it seemed to me there would be a way to capitalize on that. The Jenkinses sold some DVDs, but I don't think they ever struck it rich off catfish noodling.

We left Memphis to go back home to Kentucky, and we didn't starve — partly because we always had plenty of catfish to eat. And we took a lot of people noodling. We hosted outdoor television shows, some local, some national, and one from Canada. I wrote articles about noodling for Realtree, Field & Stream, Fur-Fish-Game, and other magazines. We filmed short videos for YouTube, and for a few springs we donated catfish noodling trips as fundraisers for Ducks Unlimited banquets.

One winter a producer approached us about filming a pilot for a noodling show he was hoping to create, an offshoot of the Animal Planet series Hillbilly Handfishin'. The plan was for various noodling teams from different parts of the country to compete in an Okie Noodling-style tournament, all filmed in a reality television format. My brother, Matt, Michelle, and I would've been Team Kentucky. But we backed out, and the show launched without us. It didn't last long. Neither, for that matter, did Hillbilly Handfishin' — it was canceled after two seasons.

Noodling, it seemed, wasn't a mystery anymore. And so maybe people were no longer mesmerized by it.

A Bunch of Old Noodlers

I've seen noodling ebb and flow in popularity a few times now — enough to know that Wade Bourne was right: People are mesmerized by it, and I think they always will be.

My buddy Ryan and I are probing the edges of a concrete flood wall, feeling for washouts underneath that might be big enough to hold a catfish. I've been fishing this wall for 15 years; some years there's holes under it, and some years there's not, I say. Always worth checking, though.

Old tattoos are on display, some real ones and some scars, from catfish and C-sections.

Ryan is still bleeding a little from a big channel cat he caught earlier in the day. You know what people at work ask me, when I tell them I'm going noodling? he says. They ask if I'm going with Hannah. I don't know who Hannah is.

Ryan is not on Facebook, Instagram, or any other social media platform, and never has been. I tell him about Hannah Barron and do my best to explain the logic of hashtags.

Hash tag? What's it do? he asks.

I don't know. I'm not sure anyone does.

Well. Hell.

I look across to the johnboats, anchored down the shoreline. There are three, and our crew is in the water, sunbaked, middle-aged, and smiling. On the one hand, I'm looking at engineers and teachers; art professors, HVAC technicians, soil conservation specialists, and marketing directors. On the other I'm looking at a hardened crowd, united by 15 summers of blood sport that's never made any of us rich but has put a couple of us in the hospital. We rarely clean fish anymore. Partly because we got burned out years ago on eating flatheads. Mostly because we'd all rather catch them again than kill them.

It's searing hot, the kind of day where you splash water onto the boat seat before you climb in because the aluminum will leave grill marks on you if you don't. Tim and Matt are probing a spot we've long called the Hoffa Hole, since it's big enough to hide a body and is the spot where we caught our first 50-pounder.

There are men and women in our crew. Old tattoos are on display, some real ones and some scars, from catfish and C-sections. Among the men there are magnificent tangles of chest hair that catch catfish slime, which dries in the sun like resin and sometimes has to be trimmed out with scissors. Middle-aged noodlers, perhaps better than anyone, know the reality of love-handle tan lines.

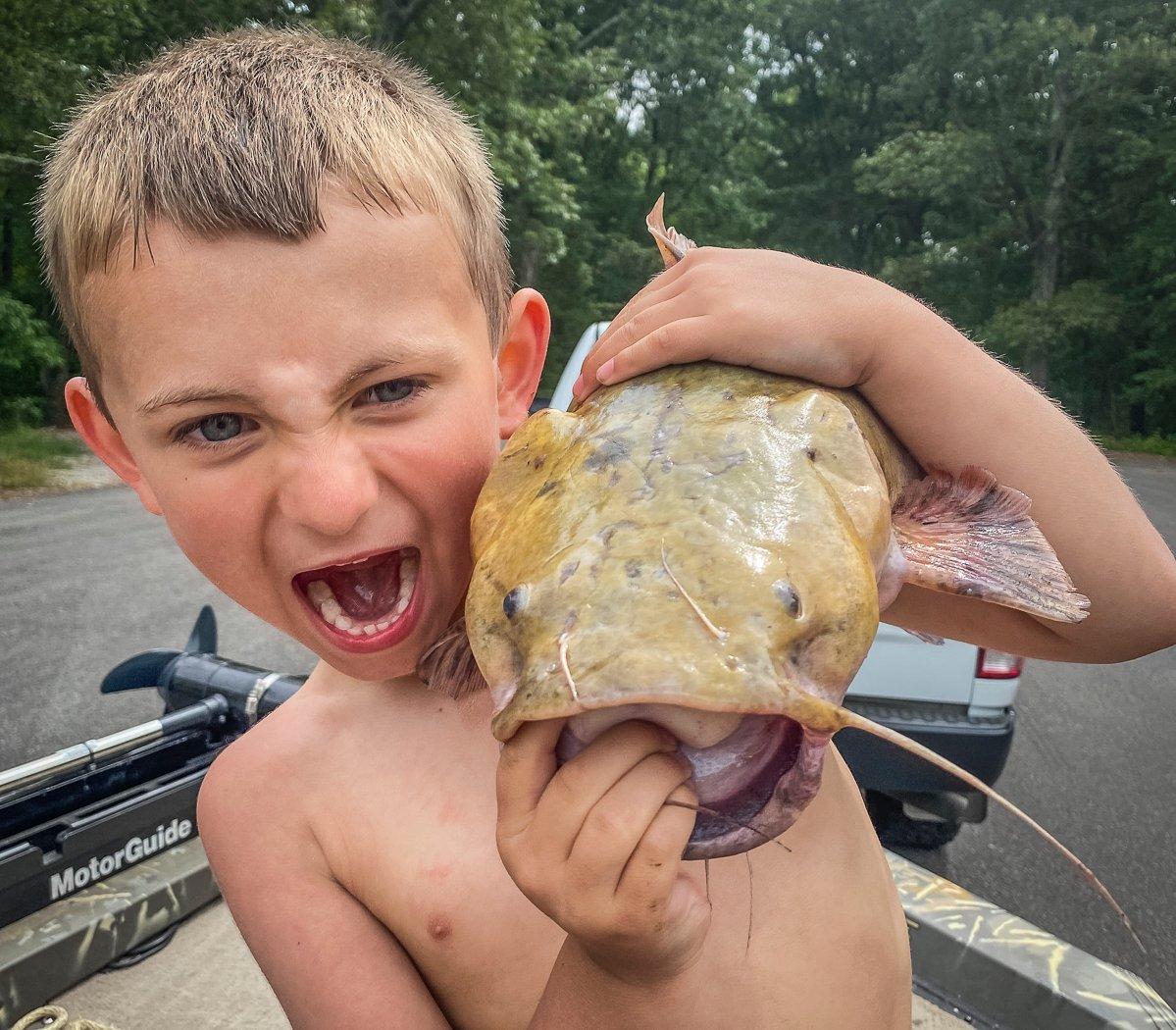

We're still full of it by day, but there's no partying and Pantera at night. We've raised kids out here. Tim's daughter, Alyssa, used to hold on to fish stringers when she was a toddler and let big flatheads pull her around in her life jacket. Now she's driving.

My and Michelle's son, Anse, likes to get his hands on big flatheads, even if he's only 7 years old and outweighed by some of the fish. The other day he helped me wrestle a 20-pounder out from under a Tennessee slab rock. There were two fish in that hole, and Anse's Uncle Matt swapped spots with us to try and catch the second one. That's the same Uncle Matt, I told Anse, who was almost famous, back in the day, for nearly filming a noodling show on Animal Planet.

I bet we have 16 more years of this in us, at least.

(Catch this Deal: Performance fishing shirt / $20 at the Realtree Store)