Do You Take Extra-Long Shots?

It seems like every rifle shooter suddenly wants to be an American Sniper. We used to think we were real riflemen when younger, taking the occasional mule deer or pronghorn at 400-plus yards. Though we practiced obsessively, we really were stretching things with the light rounds we were shooting then. But modern technology has made longer shots feasible, and by this I also mean more ethical. But there's more to long-range shooting than simply taking longer shots.

Proper equipment and preparation is paramount.

If you want to join the long-range crowd, you have some work to do to get ready.

Long-Range Prerequisites

First let's review a couple inconvenient realities. Long range is relative. For some, this might mean 400 to 500 yards. Make no mistake, that's a long poke by any measure. For others going long means much longer shots. Ultimately, how far really depends on invested practice, and being realistic about every shot. Wind drift is very real and an important factor when ranges stretch. While we don't have the space here to delve into particulars, it's a subject well worth studying if long-range shooting is your goal.

Long-range shooting also places a premium on proper shooting fundamentals. If you're a mediocre to average shot at 100 to 200 yards, adding many hundreds of yards will only make matters worse. Shooting sub-1-inch/100-yard groups off the bench is only a start. Seek assistance from an experienced shooter if needed, and keep in mind these five things.

1. The Rifle

Cartridge choice really depends on what game is targeted and how far you hope to push things. Long shots on groundhogs become 400 yards when shooting a .223 Remington, and 500-plus-yard shots at coyotes when using something in the .22-250 Remington class. For lighter big game at less than 550 yards, hotter .257s (.25-'06 or .257 Weatherby), .264/6.5mms (6.5 Creedmoor or 260 Remington), .277s (.270 Winchester), .284/7mms (.284 Winchester or 7mm Remington Magnum) or standard .308s (.308 Winchester or .30-'06 Springfield) are well suited. When ranges stretch beyond 500 yards — on any sized game — and especially on elk-sized animals, the hottest 30-calibers (300 Ultra Mag, for example) and .338s (up to the Lapua) are indicated. Those 1,000-yard shots many consider the Holy Grail of shooting demand the most powerful cartridges available, the .338 Lapua representing a minimum. It's important to understand that bullet energy bleeds off quickly past 500 or 600 yards. For example, t 1,000 yards, the .300 Winchester Magnum shooting 180-grain bullets carries the muzzle energy of .38 Special shooting a 140-grain round nose. Give that a moment to sink in. There's no such thing as overkill, so the biggest cartridges used on smaller big game isn't verboten.

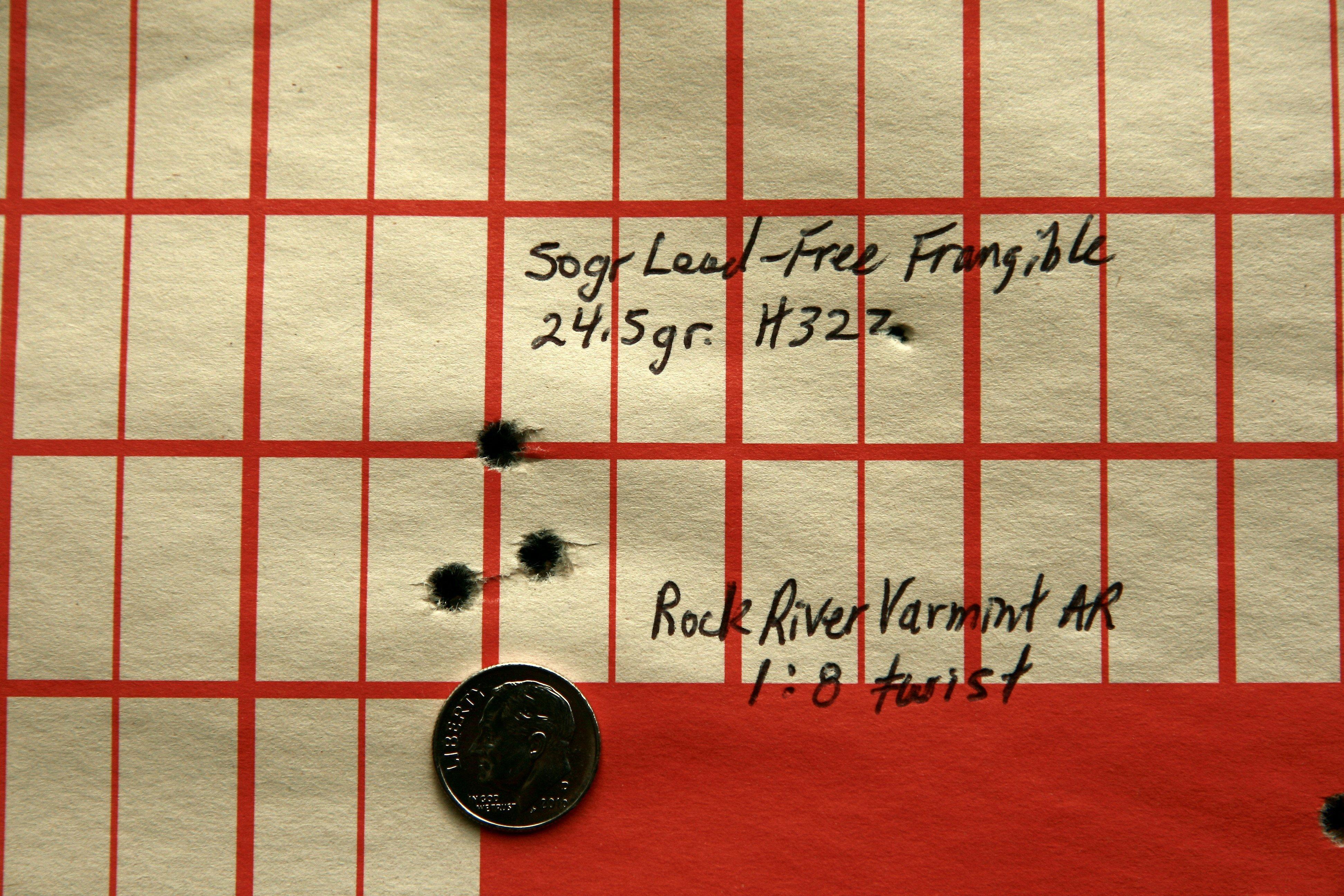

The long-range rifle should have fast (1:7 to 1:9) rifling twist and an adjustable trigger. Standard production rifling is generally 1:10 to 1:12 to handle light- to standard-weight bullets. When addressing distant targets, you want long, heavy-for-caliber bullets to assure maximum ballistic coefficients and retained downrange energy. Such pills require faster twist rates to assure stability and reliable accuracy. Savage Arms, for instance, offers such rifling in top-end Varmint and Specialty Series rifles. Or, have a gunsmith install an aftermarket barrel on your favorite rifle, normally for less than $500, all in.

A crisp, clean trigger breaking at around 2½ to 3½ pounds also contributes to long-range accuracy. Adjustable triggers are the most common avenue. Savage's better rifles come with an awesome AccuTrigger. Drop-in aftermarket models like those from Timney Triggers are another obvious solution, normally for less than $250, including instillation.

2. Better Ammo

Long-range shooting naturally leads to reloading. Factory ammo has become awesomely accurate, but only relatively, and only in the right firearm. Reloading allows you to find the precise load your rifle prefers, turning 1-inch groups into ½-inch groups. This may seem like hair splitting, but compound that ½-inch by many hundreds of yards and the difference becomes significant. Reloading also allows you to invest in the volume shooting necessary to become long-range proficient, without breaking the bank. The big cartridges, in particular, can ring up at $3.50 to $4 a shot with premium factory rounds, while reloading can reduce costs to a buck a pull.

3. Long-Range Glass

To make all of this come together you must absolutely know the range. Purchase the best laser rangefinder you can afford, while understanding advertised ranging capabilities are only viable on highly-reflective objects — billboards, metal buildings or maybe a vertical cliff. Whatever the stated capabilities of a given unit, you'll likely lose at least 50 percent in the real world. My best advice: Invest in a quality pair of range-finding binoculars. They provide more precise aiming via increased magnification, include higher-quality micro processors and are easier to hold steady (the slightest tremor causes returning laser bounces to miss the receiving mechanism). Bushnell's Fusion 1 Mile binoculars are my choice, and the most affordable rangefinder/ binocular around.

I once scoffed at scopes greater than 6X for big game. For 95 percent of the shooting average riflemen do, I'll stand by that. When ranges stretch (especially on small varmints), you'll want more magnification, and exposed windage and elevation turrets. How much power you need obviously hinges on target size and how far you'll be shooting. You can't aim confidently if you can't see your target clearly. Crosshairs that obscure more target than necessary should be avoided.

There's a world of options, but some of the scopes sitting atop my favorite varmint rifles serve as illustration. Vortex's Viper PST 6-24X50mm with EBR-1 crosshairs offers ultra-fine crosshairs (illuminated when needed), MOA internal hash marks and precise ¼-click external turrets. This is a scope precise enough I once shot a tiny ground squirrel at 468 yards — with a .17 Hornet. Bushnell's Elite 6500 4.5-30x50mm with Mil-Dot crosshairs graces my custom .22-250 Remington. This scope includes precise crosshairs and turrets, and allows me to pull off 400- to 450-yard shots on ground squirrels with relative ease. Finally, Trijicon's AccuPoint 5-20x50mm Mil-Dot is bulletproof, precise as a Swiss watch and the naturally-illuminated aiming point is a plus while concentrating on difficult shots. All include 30mm tubes, which provide additional travel for longer shots — and retail for around $1,000.

I anchor scopes to zero MOA bases. When going extra long (those 1,000-yard shots), 20 to 40 MOA bases (tilting the barrel slightly skyward for added range capabilities) and 32mm tubes provide greater range potential.

4. Rest Assured

All of this precision amounts to nothing without a proper rest. While shooting the smallest varmints, I prefer adjustable rifle cradles. I've shot a tractor-trailer load of long-range varmints using MTM Case-Gard's Predator and K-Zone Shooting Rests. They're length adjustable and include screw-adjustable front cradles for quick elevation adjustments. When I get really serious, I set these rests across a Big Game Swivel Action Shooting Bench (available through Cabela's). The swiveling seat/table allows quick response to sudden shot opportunities, and scanning for targets while glued to the scope.

5. Gaining Confidence

Shooting long comes with greater responsibilities. Gaining confidence is vital to successful long-range big-game shooting. This starts with practice. Start at the shooting range, banging the 500-yard ram until it becomes effortless. Shoot in the field, on breezy days, across canyons, filling discarded jugs with water to make shooting more exciting. Still, the best quality practice comes through small varmint shooting. While young eastern New Mexico jackrabbits are what made me a deadly big-game shot, today, high-volume ground squirrel and prairie dog shooting has become a means to an end. Believe me; a bevy of 500-round days sniping these diminutive non-game pests hones your shooting skills like nothing else. It also goes a long way toward establishing realistic and responsible maximum effective ranges to be applied to big-game hunting situations.

Click here for more guns and shooting articles and videos.

Check us out on Facebook.