Slip Up On Them Pigs and Stick 'Em

Editor's note: This article was originially published in 2007.

It's difficult to move palmetto leaves in a quiet fashion, but I was doing my best. Fortunately, it's also difficult for feral hogs to feed in a quiet fashion, particularly when there are several of them competing for the same food. The bunch I was eyeing grunted and snorted constantly, and from time to time, one of them would squeal when it felt a competitor had grabbed an especially juicy morsel. The commotion did a fine job of covering up any noise I was making. Two hours into my first-ever Florida hog hunt, and it seemed I had things wrapped up.

Twenty-five yards away, I waited as a small boar, one I could almost hear sizzling with a dry rub, turned broadside. I slowly began to draw my bow. A large, grey and white sow with a half-dozen piglets in tow saw me move and sounded her disapproval with a low, guttural grunt — an alarm call of sorts that veteran hog hunters know well. The animal, which outweighed me by a solid 50 pounds, eyed me intently, and I thought it best to wait on the draw. I got lucky because the wind was in my face. The big sow finally figured things were OK for the moment and put her head back down to feed. I was a bit nervous. There weren't many trees for climbing around, and, this being my first experience with a pack of hogs (and having seen what a pack of hogs did to Travis in Old Yeller numerous times), I didn't know what to expect.

The boar soon quartered away slightly once again, and I quickly came to full draw. Settling my top pin on its ribcage, I squeezed the trigger of my release. Unfortunately, I didn't allow for the big palmetto leaf inches in front of my arrow (but below my sight picture). It made a resounding slap when the arrow hit it, and I watched my neon fletchings fly at a sharp angle over the boar's back. I never did find that arrow.

Many factors unite to make feral hogs excellent critters for the ground-bound bowhunter, especially when stupid mistakes like the one I made are avoided. Hogs are prolific, destructive and delicious. Plus, hunting regulations for them tend to be very liberal. Florida, for example, requires no hunting license if you're after hogs on private property with the landowner's blessing.

Hogs are also relatively near-sighted, and they tend to get preoccupied when feeding. This can make stalking fairly easy to someone who is used to dealing with whitetails, but don't think for a minute the little porkers are a pushover — quite the contrary. I'd put a hog's ears and nose against a whitetail's any day of the week. To stalk a hog, it is imperative to have the wind right. Anything less simply won't cut it.

Nolan Twisselman, of Twisselman Outfitters in Santa Margarita, California, has been guiding wild hog hunters in the arid country of Central California for more than 25 years. Though he takes an ambush approach in the summer months, 90 percent of his wintertime pursuits involve spotting and stalking.

If the wind is right, you can usually get within 30 yards of a pig pretty easily, Twisselman said. The poor eyesight, combined with the numbers of pigs you'll typically see, which will give you more than one opportunity in a day, make them ideal for spot-and-stalk hunting. But if they wind you, they're gone.

Finding Hogs

Hogs can be hunted in a variety of ways and are found in states all over the country. Florida and Texas are pretty tough to beat for numbers of hogs, and a quick Internet search will reveal more hog-hunting outfitters than one could ever call in a day. Most hog trips are reasonably priced, available year-around and are a ton of fun.

Just like their domesticated brethren, wild hogs are about as tasty a critter as you're apt to shoot with a bow. Most parts of them are edible, and because the fat on a wild hog is pretty good, they don't require the intense trimming of a venison steak before being ready for the table. That fact alone, even without the glamour of a big set of antlers, makes them worth chasing.

Hog Body Language

Much like studying an angry wife after a few years of marriage, a bowhunter can learn a lot about hogs if he just keeps still and quiet and spends some time observing their behavior and body language. Just like any other big-game animal, hogs will show a variety of visual cues depending on their mood. Knowing just a few of them will make you more successful at hunting them.

They'll just freeze up, Twisselman said. They'll stop eating and stop doing everything just before they bolt.

On another warm morning in South Florida just last winter, I saw this firsthand, albeit not while stalking. I was sitting in a tree stand with bow in hand. To keep my scent to a minimum, I'd circled around behind the stand in the dark, and worn rubber boots. The ground was sandy, so hearing a hog approach was tough.

Peeking over my left shoulder after 20 minutes in the stand, a bristly black boar appeared not 15 yards from the base of my tree. He'd made scarcely a sound while approaching. The hog trotted along nonchalantly, until it suddenly slammed to a halt and cocked its ears — it had crossed the path where I'd walked in. I could hear the animal inhaling my foreign stench, and see its shiny pig nose working up and down to size up the situation. I held my breath as the hog stood like a fat, black statue, save for its breathing and twitching nose, before grunting one time and quickly trotting away into the palmettos. As it left, curly tail sticking up in the air, it didn't appear especially alarmed, but it didn't return, either. Had I known a little more about pigs, I would've had my bow in my hand and been drawn when it hit my trail and froze.

Shot Placement

If you're an avid hunter of any type, particularly an avid bowhunter, the time is going to come when you wound an animal. If there's one thing in my book that is a serious drawback to hog hunting with a bow, it's that they're tough, and their vitals are situated a little differently in their chest than a deer's. That behind-the-shoulder, two-thirds-of-the-way-down chest shot that will punch both of a broadside deer's lungs and kill it so efficiently simply won't anchor a hog in a place where you'll find it the majority of the time.

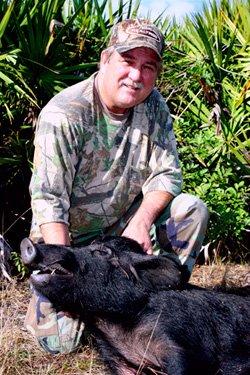

Terry Van Arkel, a longtime friend of mine who has taken more big game with a bow than most, has been arrowing pigs in South Florida for years, and he knows they're tough. But VanArkel likens the vital area to a small balloon that's located at the bottom of the chest, just between the shoulders. Pop that balloon, he says, and you'll find your hog. Align your sight pin so that the arrow will exit just behind the opposite shoulder. Most of the time, a slightly quartering-away shot is best. VanArkel rarely takes a shot beyond 20 yards on Florida hogs. He says if you're patient, a 15-yard opportunity will usually present itself.