The ‘hot rod’ cartridge of the Roaring ’20s is as relevant today as it was during Prohibition

I’m not quite old enough to remember when the .270 Win. was cool. As a Midwestern kid of the 1980s and ‘90s, the deer cartridges that got my attention were .243’s, the short-lived and barrel-burning Super Short Mags, and 7mm Remington Magnums. Though if I’m being honest, none of us liked to shoot the 7 Mag very much.

But, like red wine and Ernest Hemingway, it takes some time to appreciate the .270, which turned 100 years old this year. After dabbling with trendy calibers from the 6.5/284 Norma to the .284 Ackley Improved to every member of the Creedmoor family, I discovered the .270 on the prairies of eastern Montana when it was already an octogenarian and I was barely 20. I’ve never looked back.

From pronghorn and whitetails to heavy western mule deer and even elk, the .270 is more than up to the task. Image by Tom Tietz

My first .270 is hard to look at, but it remains the most accurate off-the-shelf rifle I’ve ever owned. It’s a left-handed Savage Model 111, produced so crudely and apparently hurriedly that the casting seams were never sanded off its black plastic stock. The gun looks lifeless, with its bulbous barrel nut and two-stage Accu-Trigger being its most distinctive features. I mounted a 2.6-16x42 scope on it and found that it shot well, no matter what bullet weight or brand of factory ammo I put through it.

I killed a pile of mule deer and Western whitetails with that rifle, plus some pronghorns and a couple elk. But its most memorable moment was on paper, a Shoot-N-C target stapled to a cardboard box which was weighted by a head-sized rock to keep it from blowing across the prairie. My dad was visiting from Missouri, and we were headed out to find him a handsome mule deer. He wanted to sight in his rifle, a restocked M1903 Springfield in .30-06, and after he got on the paper, I figured I’d confirm my zero.

Proned out on my Carhartt jacket just beyond the borrow pit of a two-track BLM road, with my Harris bipod as a front rest, I aimed at one of his bullet holes. My dad watched through binos from the pickup’s shotgun window.

“Missed,” he called.

What out-on-his-own son doesn’t want to show his dad that he’s making it, holding down a job good enough to buy a decent gun despite its appearance, and that they keep their shooting as sharp as their knife. I was rattled. How could I have missed the whole target? Maybe a little performance anxiety with the old man watching from on high.

I cranked the scope up to 16, feathered the focus, and aimed at the same bullet hole.

“Missed again.”

The break felt clean. There was wind, but not much to mention at 100 yards. I shot again. This time my dad said I had hit near his hole. It hit me at the same time – I had been printing .270-caliber holes inside his .30-caliber hole. I took two more shots to confirm, and then walked out to the box. When I returned, perforated box and target in hand, I felt not only vindicated in my skills, but I also held that homely .270 Savage in high regard.

All five of my shots had etched a neat cloverleaf in that target. My dad asked if he could study my gun for a second.

THE .270 AT A HUNDRED

My affection for the .270 was only boosted in that moment with my dad. I had already confirmed its effectiveness on almost all mid- to large-sized game out to 400 yards.

As it turns 100, the attributes that made the .270 such a disruptive cartridge are as relevant today as they were in 1925 when it was introduced to the world by Winchester Cartridge Co. as the .270 W.C.F. It’s a mild-recoiling, versatile, and generally accurate round that neatly fills the niche between the .25-caliber cartridges and the .30-06, .308 Win., and the magnum .30-caliber rounds.

First introduced by Winchester in 1925, the .270 offers a combination of relatively mild recoil and plenty of power for most large game. Image by Bill Konway

The talents of the .270 start with the cartridge itself. Winchester created the bottleneck case by necking down the .30-03, which was slightly longer than the .30-06. The smaller bore enables lighter bullets, ranging in weight from 100 to 175 grains. But the sweet spot then – as now – is the 130-grain .277 bullet. It’s light enough to produce a much flatter trajectory than the .30-06 with a good deal less recoil, but retains enough energy to put down mid-sized animals with authority. Most 130-grain bullets exit the muzzle at a skootch over 3,000 feet per second, giving them a flatter trajectory than non-magnum .30-calibers and right in line with many .25-calibers. And they achieve that flat trajectory without much recoil, enabling shooters to stay in their scope to witness hits.

Don’t Miss: THE 2025 SOUTHEAST DEER SEASON FORECAST

Now that we’re fully in the suppressor age, that last attribute might not mean much. But for those of us who grew up shooting without muzzle brakes or suppressors, most centerfire rifles jumped so badly on recoil that you couldn’t stay in your scope, especially if you turned your scope up to higher magnifications. But by keeping my scope at mid-magnifications, and shooting at mid-distance targets, I could manage the recoil and stay in my scope to see my bullet hit. That’s an important consideration for a hunter, to see how the animal reacts, and to confirm a hit or a miss.

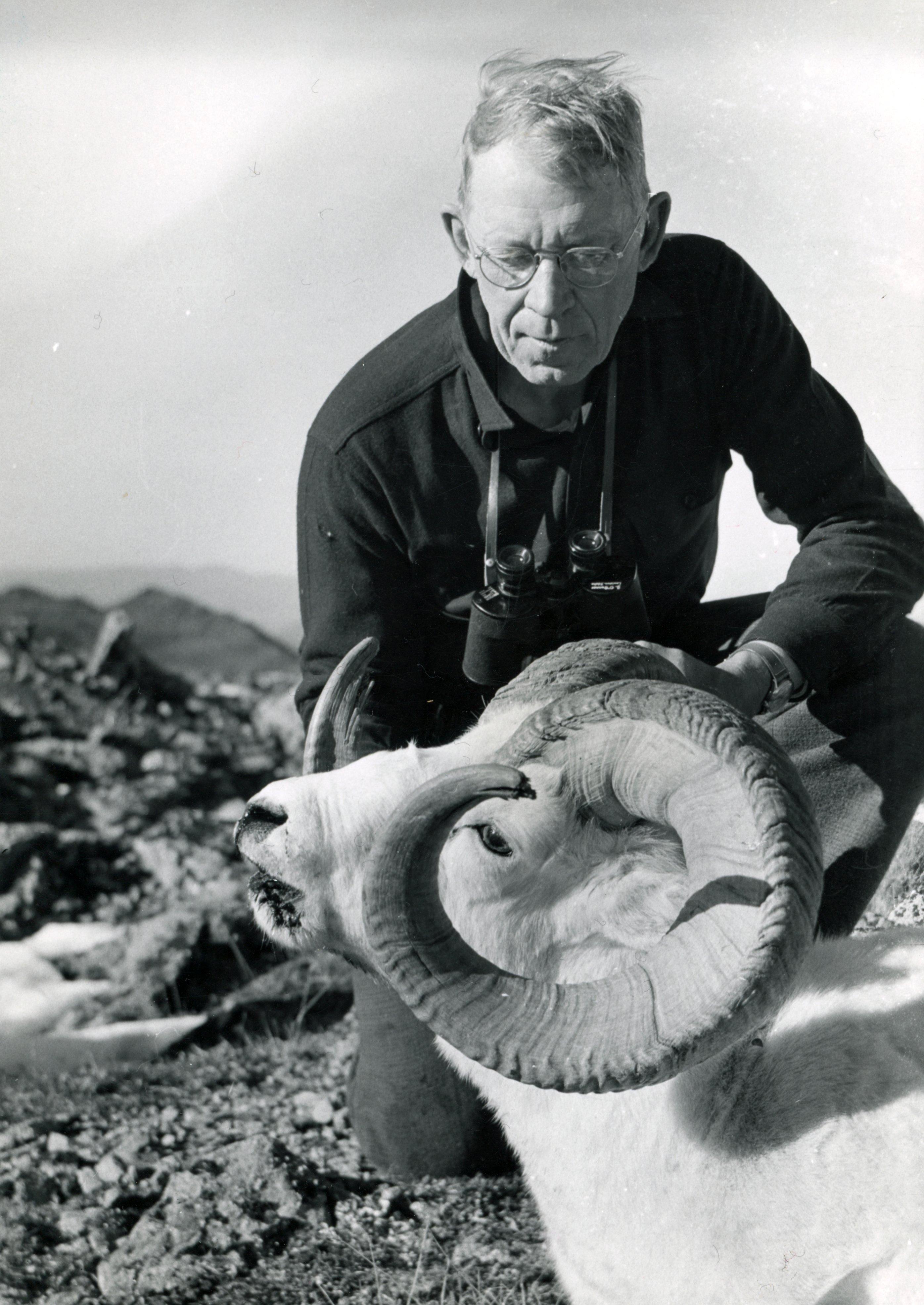

This mild-yet-lethal personality of the .270 was the ballistic balance that the first and most celebrated advocate of the cartridge, Outdoor Life’s shooting editor Jack O’Connor, observed with passion and influence.

Famed Outdoor Life shooting editor Jack O’Connor was a passionate proponent of the .270, increasing its popularity with hunters worldwide. Image courtesy of Outdoor Life

While he extolled the virtues of the .270 — flat-shooting, mild-recoiling, lethal downrange energy — it was his successes, mainly on mountain sheep, with the cartridge that buoyed its sales and spiked its influence in the middle years of the last century. It’s an open question whether the .270 would have enjoyed its success without the boosterism of JOC, but I’d like to think it would have stood on its own merits.

Don’t Miss: 3 GREAT DEER CARTRIDGES THAT DON’T GET ENOUGH RESPECT

I base that consideration on its competitors. At its introduction, and all the way up into the late 1940’s, until Roy Weatherby and lesser-known wildcatters started bringing souped-up cartridges to the market, the .270 was up against the reliable but pedestrian 7x57 Mauser and the slightly hotter .257 Roberts. There just wasn’t much else in the middle.

THE WELL-BALANCED 130-GRAIN

There must be 20 modern factory cartridges loaded behind some variation of a 130-grain .270. This is a ballistic sweet spot for the .277 bullet, with enough length-to-bore ratio to deliver a decent wind-bucking ballistic coefficient and enough retained energy to put down animals out to 400 and even 500 yards.

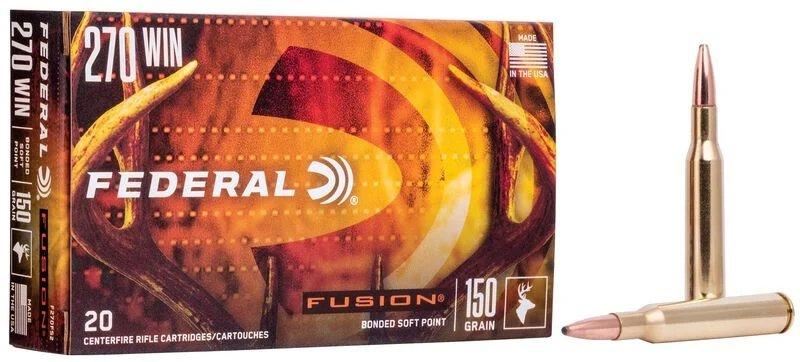

I’ve shot pretty much every 130-grain .270 in production, but the four that have routinely put down game and shot well in each of my rifles are the humble Remington Core-Lokt, the Federal Fusion Soft Point, Hornaday’s American Whitetail Interlock soft-point, and the upscale Federal Premium Trophy Bonded Tip.

One of the great attributes of the .270 is the ability to handle a wide range of bullet weights and shoot them all well. Though 130-grain bullets are most popular, some hunters prefer heavier 150-grainers like this Fusion option from Federal. Image by Federal Ammunition

But the genius of the .270 is its versatility. I have since migrated to .22-class platforms for most of my predator hunting, but the 100-grain, 3325-fps Core-Lokt is a good varmint load, though it’s a little hard on fur, and with that hyped-up velocity could be considered a barrel-burner.

On the heavier side, I shot one of my best mountain mule deer with a 150-grain Nosler Partition out of a Benelli Lupo rifle. Sierra’s 175-grain Tipped Game King is devastating on elk inside 250 yards.

The standard barrel twist for the .270 is 1-in-11, which is slow enough to stabilize its heavier bullets but can also make good work with the standard 130-grainers. The barrel twist also favors the long-for-caliber non-toxic rounds like Federal’s excellent 130-grain Trophy Copper as well as the classic Barnes Triple-Shock X bullet, also in 130 grains.

THE .270’s NEXT CENTURY

It's noteworthy to recall that in 1925, most hunters used iron sights. The relatively flat-shooting .270 probably made many notch-and-leaf shooters look pretty good by enabling them to take hold-on shots out to 200 yards. The cartridge had its next moment in the 1950s, and not only because of Jack O’Connor, but also because of the wide adoption of magnified rifle sights. Scopes doubled hunters’ effective range, and the .270 enabled longer shots.

As I mentioned, when I was a kid, I just missed one of the .270’s next “cool” moments when it became a darling of whitetail hunters just as Midwest deer numbers were surging. It’s a marvelous deer round, capable of handling a wide range of hunting scenarios where the weight of its long action isn’t a deal-breaker. I’d like to think that if my dad wasn’t so infatuated with the .30-06, that he would have been a .270 acolyte.

In the last generation, the .270 Win. has accrued more competition than ever. If it was born into a vacant niche 100 years ago, that niche is filled with semi-traditional cartridges like the .270 WSM, .270 Weatherby Magnum, and the aforementioned .280 Ackley Improved.

But in the last 15 years the .277 class has gotten even more crowded. The 6.5 Creedmoor took more market share from the .25 and .27-caliber rounds than any other. Then Nosler introduced its flat-shooting and hard-hitting 27 Nosler in 2020. Hornady promoted its high ballistic-coefficient Precision Rifle Cartridge family, including both the 6.5 PRC and the 7mm PRC, about the same time. Winchester brought its disruptive 6.8 Western to the market in 2021 as a modern version of the .270 with a short-action cartridge that boasts .300 magnum ballistics. And Sig Sauer took the prize by securing the contract for the U.S. military’s Next Generation Squad Weapon with its 6.8 SIG FURY that performs both in belt-fed machine guns and slow-fire sniper platforms.

Don’t Miss: 5 TIPS FOR GLASSING MULE DEER

But if you’re reading this then you’re probably already inclined toward classic calibers. And here’s where the .270 Win. shines. It’s a ballistic middle-of-the-roader, but more importantly, it’s earned shelf space by appealing to generations of shooters and hunters.

One of the abiding concerns of the gun-and-ammunition industry is that the profusion of new and disruptive calibers isn’t especially sustainable. How many new PRC or Creedmoor rounds can an average deer hunter afford? How many middling popular cartridges will be here in the next 10 years? While there’s an almost reactive response by American hunters and shooters to be seduced by new cartridges, ammunition for these boutique rounds can be hard to find, especially factory loads with a variety of bullet weights.

Here’s where the good old .270 shines. Walk into most sporting goods stores, from a big-box retailer in a suburban mall to a way-back country store and you’re likely to find one or more brand and bullet weight in .270 on the shelf.

You might have to blow the dust off the box, and you may have to accept a 130-grain soft-point if you’re accustomed to shooting a spiffy non-toxic load. But you’ll have shells to shoot, and you’ll have a rifle that still turns the heads of serious shooters and hunters, even 100 years on.

Maybe that’s the ultimate birthday present for the .270 Win. There aren’t very many 100-year-old American icons that we can celebrate with these essential, hopeful words: It still matters.

SIDEBAR: IS THE 6.8 WESTERN THE NEW .270?

A number of mid-caliber cartridges have tried to knock off the venerable .270 Win., most notably the souped-up .270 WSM.

But the 6.8 Western, released by Browning and Winchester in 2020, can legitimately wear the mantle of the newest disrupter. It’s intended to push heavier bullets out of a shorter barrel using faster twists, in order to work with suppressors and lightweight short-action rifles. The 6.8 Western is built on a shortened .270 WSM case and can freight bullets as heavy as 175 grains.

Muzzle velocities are just under 3,000 fps, similar to the .270, but with much heavier bullets, making the case that the 6.8 Western can handle elk- and moose-sized game. I used it last season, mainly using Browning’s 175-grain Sierra Tipped GameKing bullet and Winchester’s 162-grain Copper Impact, taking everything from pronghorn to caribou and even an interior grizzly bear in Alaska.

I’m still not getting rid of my .270 Win., but this 6.8 Western is well-suited to its namesake landscape, especially with a suppressor and longish shots on large-bodied game.

Don’t Miss: THE 2025 MIDWEST DEER SEASON FORECAST